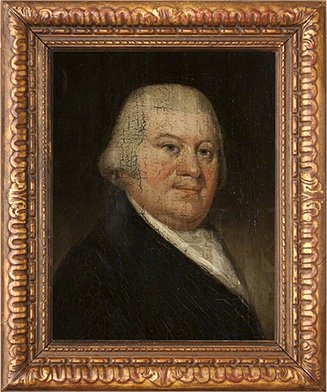

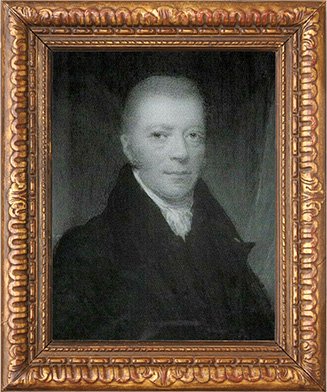

William Cross

1771 - 1827 | 7 & 11 Winckley Street

William Cross was a landed gentleman and distinguished lawyer. He was the driving force behind the development of Winckley Square. His vision of a Georgian square in Preston was inspired by the Georgian squares he had seen in London.

He married Ellen Chaffers (Ellen Cross) relatively late in life at the age of 42. He was a much loved husband and father, a benefactor and highly respected by his friends, colleagues and employees. Unfortunately William died before the Square was completed but his widow Ellen ensured his vision was realised.

The Cross family settled in Barton and Goosnargh in the 17th Century. John Cross (William’s Great, Great Grandfather) founded the John Cross CE Primary School, Bilsborrow. The school website tells us that John had provided for the school to be built, in his will written in 1718:

‘for the education of the poor children of Myerscough and Bilsborrow in reading, writing and the principles of the Christian Religion according to the doctrine of the Church of England……. My desire being to promote religion and sobriety especially in young people. And to give them an early sense of their duty to God and man, begging of God Almighty to succeed it to his honour.’

It is believed that the school was opened between 1722-23.

The Cross family, Freemen of Preston since 1700, were known to be benefactors. John Cross (William’s father) settled in Preston and was an attorney and Deputy Prothonotary for the Court of Common Pleas at Lancaster. He was known in Preston as ‘Honest John Cross’ maintaining the family reputation of being ‘sincere and genuine in their efforts to do good’.

William’s Early Years

William, born in 1771, was the only child of John Cross and Dorothea Cross née Assheton. John and Dorothea had married in 1770, sadly Dorothea died shortly after William’s birth.

Following the death of his mother William was brought up by his maternal Aunt Mary Assheton (related to the Asshetons of Downham Hall). He was educated at Clitheroe Grammar School. He then studied law at Lincoln’s Inn, London and subsequently returned to Preston where he joined his father’s law firm and they lived in a house in Fishergate.

John and William would ride together. In 1790 William, his father John and Joseph Seaton Aspden set out from Preston with their servants for a tour of North Wales. William revelled in the romantic, picturesque scenery and the noble ruins and admired the mansions of gentlemen. Mr Aspden was recorded in Agnes Addison’s diary as visiting the Addisons to talk about ‘Mr Aspden’s Rout’ when they met the Ladies of Llangollen.

The Cross Papers: Observations made upon a Tour thro’ part on North Wales Sept 1790.

A Georgian Square in Preston

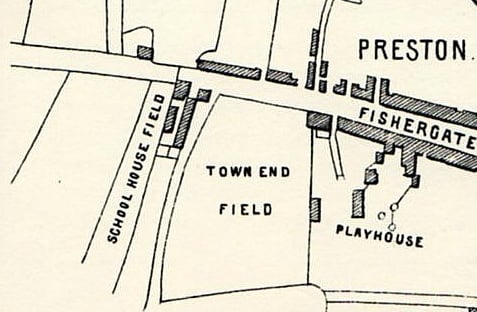

In 1796 at the age of 25 William bought Town End Field from the estate of Frances Winckley. Geoffrey Hornby, guardian of eight year old Frances acted on her behalf. Town End Field was at the end of the built up part of Fishergate. Beyond it there were country paths and open farmland.

John Cross already owned land in the Avenham area of Preston as did the Winckley family. Perhaps William Cross and Thomas Winckley had discussed the concept of a Georgian Square in Preston similar to those in London but Thomas died in 1794 so he never knew if William’s vision was realised.

William’s vision was of an elegant Georgian Square with gated gardens for the residents to enjoy. The Gardens were to be surrounded on all four sides with magnificent Georgian houses; some were in fact grand mansions.

William built the first house for himself, his father and his aunt but in 1799 when the house was ready John Cross died. William moved into the completed house with his Aunt Mary. His house was built on the corner of Winckley Street and what was to become Winckley Square. He built his house with two entrances on Winckley St. (The main entrance was number 7 now 11). To the rear was his garden (now Winckley Square Apartments).

In 1805 William, and subsequently a committee of the inhabitants of the Square, regulated the development of Winckley Square and its enclosed, locked, garden cum-pleasure ground in the middle. (William and his heir maintained a casting vote).

Winckley Square housed a ‘hefty’ proportion of Preston’s leading families, retaining them well into the second half of the 19th Century. In the 1850’s Hardwick thought that:

‘In point of extent and picturesque beauty, this provincial ‘rus in urbe’ might successfully compete with many in the metropolis’

Hewitson commenting on Winckley Square in the 1880s said then the centre:

‘has beautifully-umbrageous, pleasantly-floral appearance- has an emerald charm and propriety of culture about it suggestive of select country ground rather than of sub-divided town land, within a good stone throw of a busy, tram-wayed street, in the heart of a large borough’

To read more about how William and Ellen managed the development of Winckley Square go to the Regulations of Winckley Square area of the website.

Bachelor life

On his father’s death William Cross was appointed Deputy Prothonotary for the Court of Common Pleas at Lancaster, the position occupied by his father. He was also deputy lieutenant of the County. He was 29 years of age.

William was an active member of Preston society, organising the Volunteers during the wars with France. In 1797, because of the threat of invasion from Napoleonic France, a regiment of Preston Royal Volunteers had been raised by Nicholas Grimshaw. William Cross was commissioned Lieutenant in 1797 and Captain in 1798 in the Royal Preston Volunteers and later the Militia

William helped to create a social circle of gentlemen and their ladies in the town which ensured that the town retained its reputation as the focus of county society. He was on dining terms with the local notable families. He attended assemblies, plays and concerts.

He was deeply religious and attached to the Church of England; three generations of the Crosses were very generous benefactors to the Church. William was an intimate friend of Rev. Roger Carus Wilson; taking an interest in church extension and assiduously attended the meetings of the Missionary and Christian Knowledge Societies.

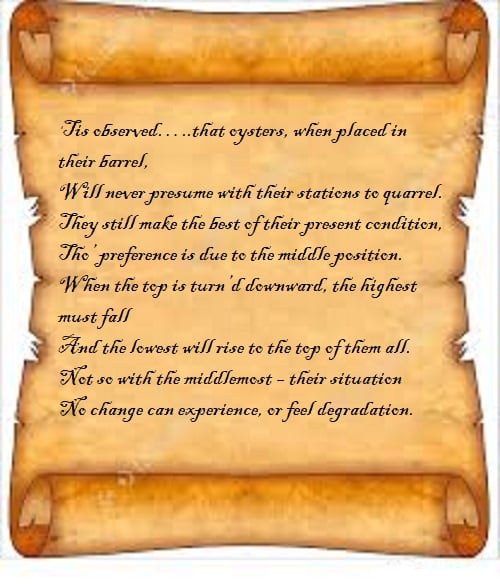

The Oyster and Parched Pea Club

There was in Preston at this time a Club, exclusively for gentlemen –‘The Oyster and Parched Pea Club’. Its members, who were among the town’s leading citizens, met weekly at each other’s houses. The Club had many officers, such as:-

Cellarius, who had to provide port of the first quality;

Oystericus, who was in charge of the oysters;

Clerk of the Peas, an office always held by a member of the Gorst family, and

Rhymesmith, William Cross, who had a great talent for verse. Marian Roberts suggested he might be the author of the following verse written in 1806:

In the records of the Preston Oyster and Parched Pea Club (1773-1841) in 1808 the Rev.Thomas Wilson, in his capacity as deputy Rhymesmith, wrote:

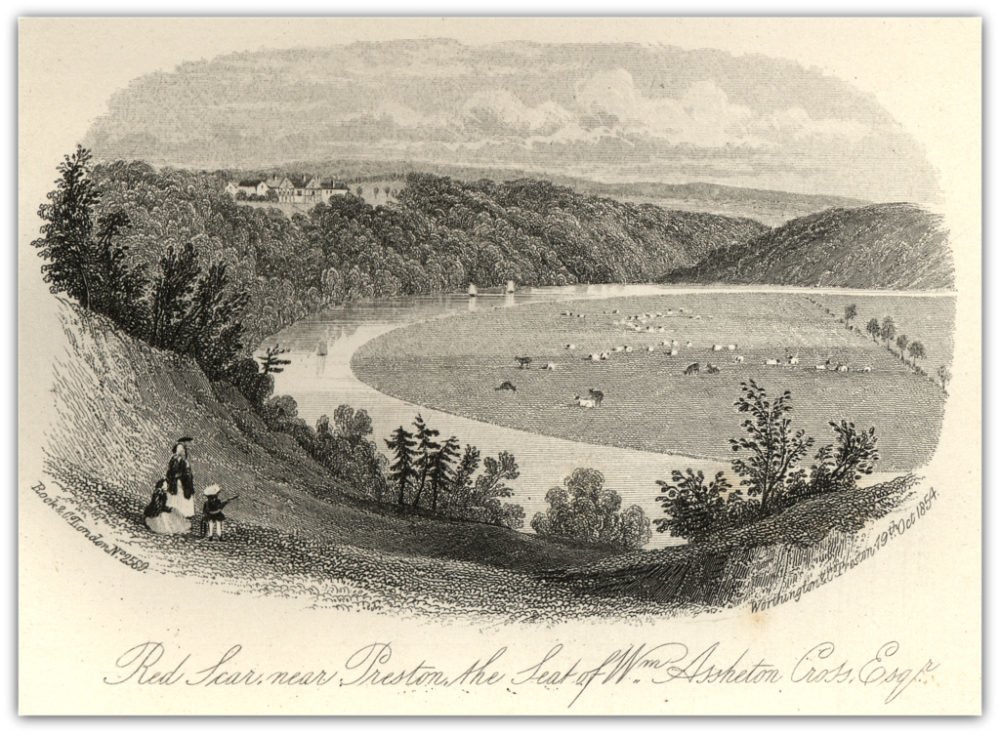

Red Scar Estate

William enjoyed the countryside and travelled extensively on horseback. Whilst riding he fell in love with the view of the Ribble at Horse Shoe Bend on the ‘Sweet Ribble’ as he called it. Long before the house in Winckley Square was completed William bought the run down historic thatched Red Scar Cottage. There was much evidence that part of it was simply a farmhouse in days past, with an old brew house, brick boiler, dairies, stables, and byres leading onto a cobbled courtyard.

William never tired of the views of the land and the river from which Red Scar took its name following a number of landslides that unearthed red earth on the steep banking around the Horse Shoe Bend.

The cottage was enlarged and altered in 1798 and he spent most of his weekends there, going to church at Grimsargh in the mornings, often walking home by Elston through the woods and to church at Samlesbury – by boat – in the evenings.

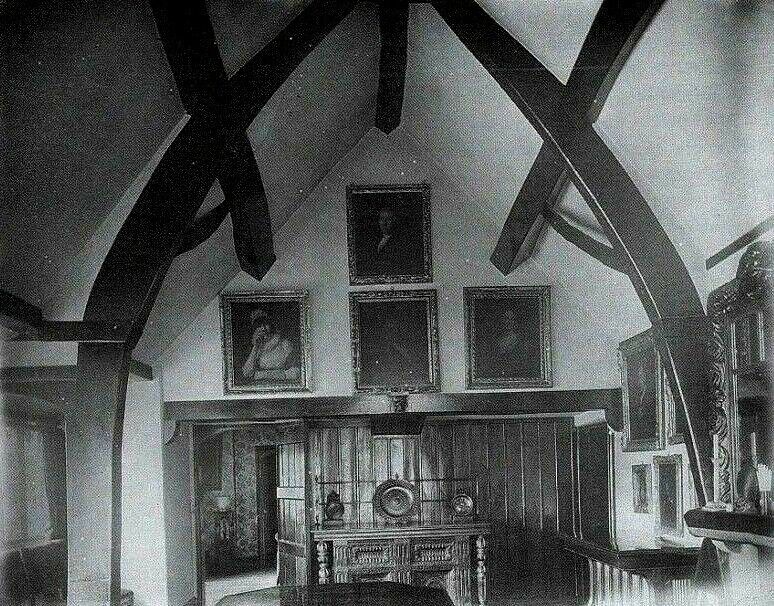

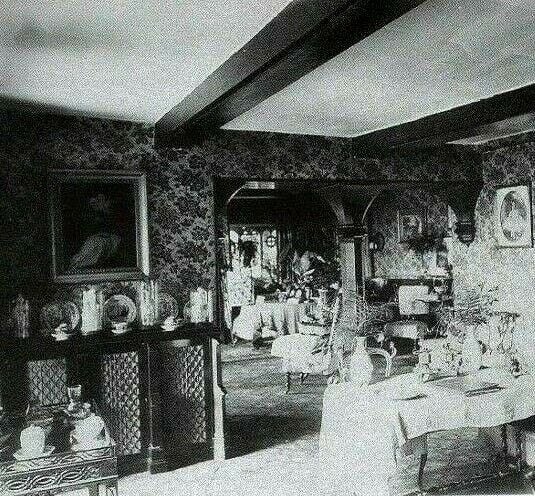

William extended the building and the estate by buying land in Elston, Grimsargh, Brockholes and Ribbleton. William remodelled the original cottage into Red Scar House, an Elizabethan-styled house of magnificent proportions. Probably out of affection for the small cottage he incorporated it with its thatched roof into the grand mansion.

The thatched one storey wing at the northeast end, used as a dining room, preserved an ancient feature. This thatched wing was believed to have been a church originally. A large, blackened with age, carved oak table was believed to have been the altar and two old wooden candlesticks remained from early days.

The interior of Red Scar contained much fine oak furniture, including a massive black oak court chest bearing the date 1368.

In 1804 William wrote to his friend John Gorst who lived in the fifth house to be built on the north east side of the Square. He tried to persuade him to purchase land and become his neighbour on the ‘Sweet Ribble’

Dear John

I am amusing myself here today with a few spademen, and after a good snack of oatcake and buttermilk I have prevailed upon myself to sit down for a few minutes, and cannot better employ them in reminding you of the scheme once laid down for you becoming my neighbour upon the banks of this sweet river. There is now an estate which I understand might be bought ere long, if the price could be agreed upon. The edge of the bank is very beautiful and commands a noble view of the river and the valley.

Yours ever most faithfully,

W.Cross

Lord of the Manor of Alston

The manorial rights of this area of land were long invested in the Hoghton family and in 1803 William bought the manorial seat Grimsargh with Brockholes for £630 from Sir Henry Philip Hoghton, 7th Baronet of Walton Hall and Hoghton Tower. He became Lord of the Manor in 1807 later succeeded by his son William Assheton Cross, William Cross (son of William Assheton Cross) and finally Katherine Mary Cross in 1916.

Red Scar House stayed in the Cross family for over 200 years. Katherine Mary Cross sold it to Courtaulds in 1936. Courtaulds textile factory was a significant employer in Preston from 1939 to 1979 when it closed with the loss of 2,600 jobs. It is now an industrial estate.

Marriage of William Cross and Ellen Chaffers 1813

In 1813, when William was 42, he married Ellen Chaffers,30, of Liverpool and it was at this point that he sold his Winckley Square home to the Addisons and took up residence permanently at Red Scar.

Ellen and William enjoyed marital bliss and loved the beauty of the countryside. William wrote to his friends ‘ …no man has ever had a more happy marriage’. The family spent idyllic days there, walking through the woods to Elston and sailing across to Samlesbury. The family also enjoyed spending a week or two in Southport.

William was involved with his work, the political life of the town, creating Winckley Square and continued to be absorbed in his work for the various churches.

Between the years 1816 and 1826 William and Ellen had 6 children.

William dies suddenly 1827

William and Ellen were married happily for 14 years. Sadly his life came to an abrupt end on 4th June 1827 when at the age of 56 he caught a chill and his lungs became inflamed. It was medical practice then to ‘bleed’ the patient. Bloodletting is the withdrawal of blood to cure illness.

The sadness felt by his family and friends is expressed in letters which David Hindle reproduced in his book Grimsargh: The Story of a Lancashire Village: Sam Staniforth of Storrs, Kendal wrote of William’s death to an associate on 14th June 1827:

‘Oh my dear friend, how shall I tell you what we have all suffered from the moment I sent off my letter communicating the alarming illness of your valued friend, Cross, to the rapid close of his precious existence at quarter past three o’clock. All were around him to witness his peaceful end – which was only ceasing to breathe.’

Canon Parkinson wrote of William Cross:

‘He loved beauty of every kind, whatever was beautiful because it was beautiful, Gothic architecture, music – Handel and Mozart – were his delight – the same in scenery. The will of his God was the law of his life, in small as in great occasions. No one ever heard from his lips a calumnious censure or ill-natured remark. He was never so happy as at home, but all his domestic pleasures were mixed up with religion and hallowed by it. If a child was born to him we find an entry in his Bible with the addition, ‘Laus deo’ (Praise be to God) and if he came from a long journey and all went well the words are still the same.’

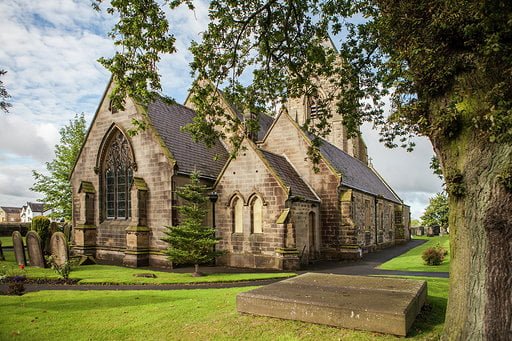

Everyone in the town mourned his passing. William Cross is buried in the chancel of Grimsargh Church

Ellen was widowed at 44 with six children aged from 7 months to 11 years. With the help of her three sisters and staff she managed the completion of Winckley Square; realising William’s dream of an elegant Georgian Square in the centre of Preston. She managed the Red Scar estate and ensured their children received a good education and achieved their potential.

It became Ellen’s role to implement the ‘The Regulations of Winckley Square’ that applied to the building of houses on the Square. She ensured the grandeur of the Square was realised.

Ellen died in Grimsargh on the 27 January 1849 at the age of 65. Both her daughters, Ellen and Ann, died before her.

St Michael’s Church commemorates the Cross family with eleven brass plaques on the wall and floor of the chancel and a fine memorial brass over the Chancel burial place of William and Ellen Cross. The memorial measures 8ft x 4ft. William is portrayed in his lawyer’s gown and Ellen in Victorian matron’s dress. It has a gothic canopy inlaid with shields and ornamented with allegorical figures. It is engraved with the words,

‘A good man leaveth an inheritance to his children’s children. She opened her mouth with wisdom and in her tongue was the law of kindness. Here lie the remains of William Cross, Esq., born 24th July, 1771, died 4th June, 1827, also the remains of Ellen, his wife, born in December, 1783 – died 27th January, 1849. Their four sons erected this monument.’

A carpet is laid over the memorial brass to preserve this wonderful memorial to the lives of William and Ellen.

Their 3rd son, Richard Assheton Cross, 1st Viscount Cross, GCB, GCSI, PC, FRS (1823 – 1914) born in Red Scar. Known before his elevation to the peerage as R. A. Cross. He was a British statesman and Conservative politician. He was MP for Preston (1857-62) and later for S W Lancashire from 1868. He served as Home Secretary between 1874 and 1880 under Disraeli and from 1885 to 1886 under Salisbury.

Read more about Ellen and the Cross children

Many of the roads in Preston are named after the notable residents, many of whom lived on Winckley Square. Cross Street is named after the Cross family. The family were an intrinsic part of Preston’s history and William’s and Ellen’s descendants continued their good works. During the cotton famine Katherine Matilda Cross collected several hundred pounds and with the money bought blankets, and other creature comforts to distribute among the starving poor.

Useful Sources

Many thanks to David Hindle and Keith Johnson for their generous support sharing their research, providing manuscripts and photographs.

The Oyster and Parched Pea Club 1861: Images provided by Peter Wilkinson

Online sources Ancestry, Find My Past, British Library Newspapers and The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography which are available through Lancashire Libraries and Lancashire Archives.

Lancashire Archives: The Cross Papers: Observations made upon a Tour thro’ part on North Wales Sept 1790.

David Hindle’s Life in Victorian Preston (2014) & Grimsargh: The Story of a Lancashire Village (2002) detail the life of the Cross family in Grimsargh.

Keith Johnson: Secret Preston (2015)

Marian Roberts’ The Story of Winckley Square, which is available through Lancashire Libraries, was a key resource as was The Marian Roberts Collection at Lancashire Archives.

Brian Lewis: The Middlemost and the Milltowns: Bourgeois Culture and Politics in Early Industrial England (2001).

Anthony Hewitson History of Preston 1883

Charles Hardwick history of the Borough of Preston and its Environs, in the County of Lancaster (1857)

By Patricia Harrison