Louisa Frances Walsh

1854 – 1909 | 1a Chapel Street

Early years

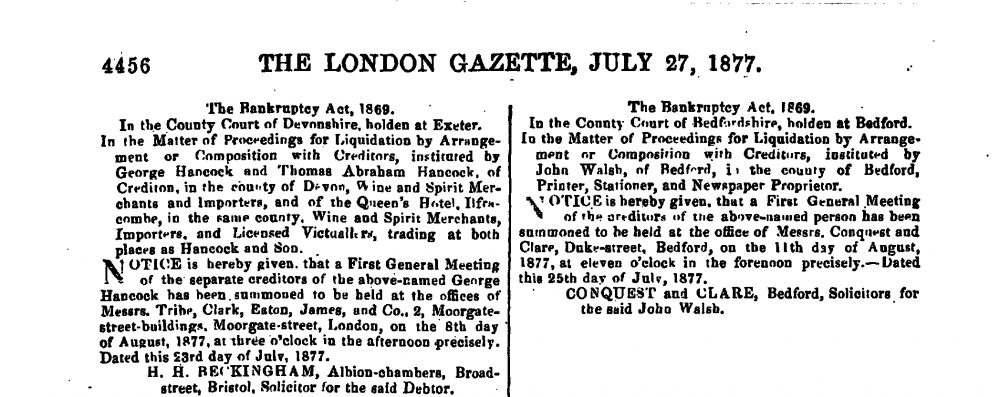

Louisa was born in 1854, the fifth daughter of John Walsh, Printer, Stationer and Newspaper proprietor of Bedford. The family employed no servants but by 1877 John Walsh was bankrupt.

Too high up the social ladder to earn her keep by working in a shop or factory, Louisa took the only employment suitable for her status: that of a governess. By the age of 16, Louisa was responsible for the education of four school-age children of a family in Bedford, teaching them the ‘ three Rs’ in return for a small salary on top of her board and lodging.

At the same time, she took advantage of a government initiative to promote learning in the sciences:

‘A sum of money is voted annually by Parliament for scientific instruction in the United Kingdom. The object of the grant being to promote instruction in Science, especially among the industrial classes, by affording a limited and partial aid… towards the founding and maintenance of Science schools and classes. The following are among the Sciences… (funded for instruction):- Acoustics, Light, Heat, Magnetism and Electricity, Inorganic Chemistry, Organic Chemistry, Geology, Mineralogy, Mining, Metallurgy.

The assistance…is in the form of… Public Examinations, in which Queen’s Medals and Queen’s Prizes are awarded’

The Chemical News and Journal of Physical Science by William Crookes 1867

In the German room of the Commercial Schools in Bedford, Louisa attended evening science classes under the tutelage of Mr. Alfred W. Glover. She studied Physical Geography and Magnetism and Electricity, taking examinations in both. The examination papers took the form of printed questions sent in sealed envelopes from the Science and Art department in South Kensington, London. In 1871, Louisa passed both subjects securing a second class certificate in each. (The Bedford Times and Bedfordshire Independent 04.07.1871)

There is no evidence to suggest that she continued her evening class studies beyond 1871, but at some point she left her position as governess and secured employment firstly as Assistant Mistress at the Norwich High School for Girls and then as Second Mistress at the Exeter High School for Girls. (The Preston Guardian 07.01.1878)

Headmistress: Preston High School for Girls

In 1877, at the age of 28, Louisa took up the position of Headmistress at the new Preston High School for Girls which opened its doors to pupils in September 1878. She lived in the school building overlooking Winckley Square along with Eliza Finbar, cook; Mary Scott, parlour maid; and Eliza Pike, housemaid. All three servants came from Devon to the new school in Preston so it is highly likely they had worked with Louisa at Exeter High School for Girls.

The school was privately funded through the issue of shares and governed by a council of local dignitaries including: The Lord Bishop of Manchester (Visitor), the Venerable Archdeacon Hornby (President), Mr. Edmund Birley (Vice President), Mr. W. P. Park (Hon. Treasurer), Rev. G. Steele (Hon. Secretary and Preston Schools Inspector) and eight other council members. The school advertised the fact that Miss Walsh was assisted by a number of Masters and Mistresses who had passed University examinations; it offered tuition in Divinity, Mathematics, Composition and Literature, Ancient and Modern History, Geography, French, German, Latin, Natural Science, Logic, Political Economy as well as those studies deemed essential for a future wife and lady: Domestic economy, Drawing, Class singing, Harmony, Needlework and Callisthenics. (Preston Guardian 07.01.1878)

The school’s aim was to provide a good education to girls whose parents had limited means or who did not want to send their daughter away to boarding school. (The Preston Chronicle and Lancashire Advertiser 14.12.1878)

In Victorian times, higher class (and professional/merchant class) girls were educated at home by a governess or were sent to a boarding school where the curriculum was designed to prepare them for life as a wife, home manager and mother. Lower-middle-class girls (like Louisa) were educated by their parents, usually the mother, up to the age of ten when they attended small, local day schools for about four or five years. Their levels of achievement were particularly low.

Frances Mary Buss was the founder of the first girls’ secondary school: North London Collegiate School, which opened in 1850.

Mary was a campaigner for women’s rights, believing that an academic (rather than a social) education for girls, to the same standard as that offered to boys, was essential ‘for any position in life which they may be called upon to occupy’.

Soon, schools charging affordable fees, owned by companies and run by a committee or council of governors, sprung up across the country. The Preston High School for Girls was one of the first in Lancashire.

From the very beginning, the school council made a point of emphasising the fact that the school’s doors were open to girls from any social class (whose parents could afford the fees!). They recognised that some parents might have concerns about their daughters mixing with those from lower classes The Venerable Archdeacon Hornby, at the school’s first prize-giving ceremony in December 1878, reassured parents with the highly improbable statement:

‘they (the girls) came to the same school, sat in the same room, partook of the same instruction and were taught by the same teachers; but it was probable, nay, more than probable, that a girl sitting at one desk did not even know the name of the girl sitting by her side.’

Preston Chronicle and Lancashire Advertiser 14.12.1878

Reference was made to the school rules including one ‘enjoining strict silence during school hours’, which would certainly prevent any possibility of collaborative learning, so popular today. The council praised Miss Walsh for her ‘tact, energy and ability’, further stating that she had more than fulfilled their expectations. (ibid)

By July 1880, the number of pupils on roll had increased from 60 to 119 and the school was up to capacity for the size of the building. The school council heaped high praise on Miss Walsh at the speech day ceremony saying that:-

‘(they) had the greatest satisfaction in having secured the services of a lady who had had a thorough knowledge of the mode of training youth, both at the High School for girls at Norwich and Exeter, of a lady, who, almost to the injury of her health, took so much interest in her work that her whole life seemed to depend upon the advancement of the children of the school…’.

The Preston Guardian 31.07.1880

A Very Public Disagreement

A small number of girls were being entered for Oxford local examinations alongside the boys from Preston Grammar School in Cross St. and were having some success in subjects such as Religious Knowledge, English History and Literature, French, Geography, Drawing and Shakespeare and Bacon.

Lord Winmarleigh, who presented the prizes, made reference to the value of education for women, stating that if women should ever achieve their objective of obtaining the vote, they would have need of a good education and he continued:

‘if it so happens that a female in the town of Preston should come to have municipal or parliamentary privileges (laughter)… they would not be worse for giving their votes for the education that they received in these days… (laughter and applause)’

The Preston Guardian 24.12.1880

There was however, a dark cloud looming on the horizon. A disagreement between Louisa and the Rev. Alfred Beaven Beaven, Headmaster of the Preston Boys’ Grammar School, became very public when it was reported in great detail on the 19th August 1882 in the Preston Guardian.

Rev. Beaven had issued a pamphlet containing letters which had passed between him and the Rev. G. Steele, honorary secretary of Preston High School for Girls and HM Inspector of Schools. The content of those letters was reproduced for all to see.

The argument centred on the fact that Rev. Beaven had contradicted Miss Walsh’s professional judgement. Miss Walsh had entered two of her pupils for Oxford local examinations in certain subjects. The girls’ parents had consulted with Rev. Beaven, who gave the opinion that the girls should be entered for more subjects and he had arranged for private tuition by Grammar School masters without consulting the girls’ Headmistress. The girls succeeded in the exams.

Rev. Steele wrote to Rev. Beaven to ask if he had recommended the extra subjects, to which Rev. Beaven declined to answer stating that Rev. Steele had no right to pose the question. He also complained that Miss Walsh had been rude to Mrs. Beaven. Rev. Steele replied that Rev. Beaven seemed to think that he had a right to interfere in Miss Walsh’s professional decisions simply because he held the post of a Headmaster and without doing Miss Walsh the courtesy of informing or consulting her. He then felt that he had the right to complain of a lack of courtesy by Miss Walsh to himself and his wife. Miss Walsh was very naturally aggrieved and had taken it as a slight on her professional fitness.

What is very clear from the reports of the correspondence, is that Rev. Beaven’s tone throughout was sarcastic and implied superiority. In one letter he questioned Miss Walsh’s qualifications, saying that he could find no evidence of them (in contradiction to that of her colleagues). He inferred that Miss Walsh was of a lesser social and intellectual culture than himself; that he had more extensive knowledge and longer practical experience than ‘she can lay claim to’ or ‘possibly possess’. He said that he had heard reports that she had written to the Bishop and Headmasters of Harrow and Clifton to secure sympathy; that she had been seen walking in Avenham Park on Summer evenings with the schools’ inspector (Rev. Steele), talking in an ‘earnest and excited manner’.

Miss Walsh re-issued the disputed school regulation 12 in June 1882:

‘no pupil will be allowed to enter for a public examination without the consent of the Headmistress nor to take any other subjects than those selected by her. When private instruction is required in preparation for such examinations, it will be given by teachers of the school staff. Signed by L. F. Walsh Headmistress.’

Rev. Beaven declared that he was not in the least concerned if Miss Walsh’s edict was obeyed – in fact it would lighten his workload for which he had received no remuneration in any case. He said that if parents listened to Miss Walsh’s ‘whines and private jealousies’, they had less common sense than he had allowed them. Miss Walsh could ‘bite off her nose to spite her face’ if she chose but could not expect intelligent people to follow her.

He even made a personal attack on Rev. Steele with a snide insinuation as to his motives in supporting Louisa:

‘ I cannot help expressing my surprise that a gentleman whose gallantry leads him to commit himself to the undiscriminating championship of a lady with whom he has no ties of consanguinity (blood relationship) or affinity, cannot better understand and sympathise with the indignation of one whose wife has been subjected to a premeditated but unprovoked attack. Perhaps, however, it is too much to expect that one who has not yet, however qualified by age and gravity, assigned the role of Benedick can resist the temptation to occasionally condescend to the part of Romeo’.

The Preston Guardian 19.08.1882

Louisa resigns her role as Headmistress

One can only conjecture at the effect that this very undermining and humiliating public spat had upon Louisa, but eight months later, in February 1883, the Preston Guardian reported that a new Headmistress had been appointed, following the resignation of Miss Walsh.

By September 1884, Louisa had moved to Plymouth to become Headmistress of Devonport, Stoke and Stonehouse High School for Girls.

At the annual prize-giving ceremony in November of 1884, it was noted that the school council had:-

‘secured the services of a lady…….well fitted to advance the interests of our school by increasing the numbers and the high repute to which it has attained’.

The Western Morning News 17.11.1884

In fact, Louisa only held the appointment for 2½ years during which time she met her future husband, Charles William Robinson. He was an excellent tenor singer and Professor of Music of Falmouth, Devon. He directed public concerts and earned his living by giving private tuition. Seven years older than Louisa, Charles was a widower with two young children when they married on 1st January 1887.

The 1891 census shows that they had been blessed with two sons in 1887 and 1890; a daughter was born in 1894. It is interesting to note that although she was no longer working, she still recorded her occupation on the census record as ‘Headmistress High School’.

Louisa died on 5th April 1909 from Breast cancer at the age of 55.

And What of Rev. Alfred Beaven Beaven?

Mr Beaven, as Headmaster of Preston Boys’ Grammar School, continued to make an occupation of writing to newspapers. A researcher of history, he detested inaccuracy and fired off letters commenting, correcting, bemoaning and complaining on all manner of subjects.

He might have done better to concentrate on living within his means for, on at least two occasions, he nearly came to grief through non-payment of debts.

On 15th October 1887 the ‘Affairs of the Rev. Alfred B. Beaven’ were reported in the Preston Chronicle and Lancashire Advertiser when a meeting of his creditors was held to discuss and agree a plan of action. The Grocer and founder of Booths supermarkets, Mr. E. H. Booth, presided. It was stated that:-

‘the majority of creditors considered the Rev. A. B. Beaven was a clever man, but in some things he lacked considerably. Mr. E. H. Booth made use of a much stronger expression.’

All parties agreed to take a reduction in their debts in order to allow him to clear them. (The Preston Chronicle and Lancashire Advertiser 15.10.1887)

Six years later, Rev. Beaven was in hot water again when a local butcher took out a commitment order against him for non-payment of debts. (A court order that states a person must be kept in custody). In his defence it was stated that Rev. Beaven had been trying to wipe his debts but was not now in a position to meet the liability. The judge made the commitment order for 20 days, suspended for 1 month. (The Preston Chronicle and Lancashire Advertiser 09.12.1893)

James Heppel’s ‘History of Preston Grammar School’ (1996) provides details of what David (Charlie) Billington describes as ‘the disastrous reign of Alfred Beaven Beaven’ in his chapter on the school in ‘A Portrait of Winckley Square’ (2018).

Beaven achieved good examination results but was detested by pupils. Noted for his use of the cane, he oversaw a steady but astonishing decline in numbers from 137 in 1882 to 32 in 1898. This compared unfavourably with Louisa Walsh’s success in filling her school. He was given the equivalent of 12 months’ notice to turn the school around but failed to do so. He pleaded poverty to the Committee when he resigned and they recommended he be given £250 for his family. The Council decided otherwise and he was on his way without any reward.

Sir Charles Holmes, later Director of the National Gallery, was a pupil of Beaven’s and this was his description of Beaven in Heppell 1996:-

‘With his dark beard, beetling brow, eyeglass screwed tight into his right eye, and his reputation for flogging’

Charles Holmes was sent to Beaven for lying and was to receive ‘ten cuts of the cane’. After six strokes he felt ‘unbearable agony’. He promised never to lie again if he could be excused the other four. Beaven refused, chuckled and caned him four more times. Charles later said he was pleased Beaven had not accepted his offer never to lie again! Heppell p.58

Rev. Beaven moved to Leamington Spa in 1898 to open Greyfriars Preparatory School. He died on 10th March 1924 at the age of 77, still working as the school’s Principal. (The Royal Leamington Spa and Warwickshire Standard 21.03.1924)

Useful Sources

The Chemical News and Journal of Physical Science by William Crookes

http://www.british-history.ac.uk/

English Heritage Blue Plaques,

By Susan Douglass