Henrietta Miller

1852 - 1926 | 5 Winckley Square

Henrietta Mary Miller filed for a divorce from her violent and abusive husband at a time when legislation made it more difficult for women than for men to divorce their spouse. Many women stayed in unhappy marriages because the cards were stacked against them.

Henrietta’s early years

Henrietta Mary (known affectionately as ‘Minnie’ by her family), was born on 2nd March 1852, the eldest daughter and third child of Thomas Miller, the major shareholder of the Horrockses textile company and an Alderman of Preston borough.

Alderman Thomas Miller Minnie’s father

The Miller Album: Harris Museum, Art Gallery and Library

Thomas and his wife, Henrietta Sarah, who was a niece of Samuel Horrocks, had lived at number 3 Winckley Square and then number 7 Winckley St. since their marriage in 1841. In 1854/5 Thomas built a grand new mansion house in the Italian Palazzo style in the North East corner of Winckley Square: number 5.

Here, the Miller family was Victorian ‘nouveau riche’, living an extremely comfortable life, with a butler, cook, housemaids, children’s nurses and a governess catering for their every need.

The family also had other residences including a sea-side home at 3, West Beach, Lytham which was a retreat from the smoke and grime of town life and where they spent summers. The Millers mixed socially with families of their class both in Preston and Lytham and Minnie enjoyed the friendship of her contemporaries in both venues.

Thomas Miller died in 1865 when Minnie was nearly 13 and two years later her eldest brother Thomas Horrocks Miller became head of the family on reaching his majority, inheriting the main Miller estates and assets. Minnie and her sisters inherited £30,000 each (approx. £3.5 million today).

Minnie’s marriage to Sutherland Dumbreck

Minnie grew into an attractive young woman and at some point met her future husband: Sutherland Dumbreck, a gentleman of London and Sussex, one year younger than her, a former student of Harrow School and the only child of Sir David Dumbreck, Inspector General of Army Hospitals and Honorary Physician to Queen Victoria.

They married on 2nd September 1873 in Preston Parish Church; Minnie was 20 years old and Sutherland was just one month short of his 20th birthday. The wedding was extremely lavish with a whole column devoted to it in the Preston Chronicle and Lancashire Advertiser 6th June 1873

“Hitherto the morning had appeared but gloomy; but at this time the sun shot forth, and it was a pleasing sight, as the rays pierced the stained glass windows, and lit up the chancel, to behold the bridal couple and their attendants, who, with bowed heads and genuflected knee, listened to the telling words of the minister and prayed for a happy union…..”

The happy couple joined their guests at 5 Winckley Square for the wedding ‘dejeuner’ before setting off on the afternoon train to London for their honeymoon and life together. That evening, a grand ball was held at 5 Winckley Square to celebrate the nuptials.

The place of a married woman

Now it must be remembered that Minnie was in possession of a fortune and in 1873, as far as the law was concerned, on marriage, all that she owned became his. The philosopher John Stuart Mill described a married woman’s position in his 1869 essay ‘The Subjection of Women’:

“The legal position of married women for most of the nineteenth century was little short of that of a slave. As soon as a woman married she disappeared as far as the law was concerned; now she was no longer a person in her own right but was merely an extension of her husband, unable to own property or even her own person. A woman became essentially a chattel of her husband; her wealth and possessions were now all his”.

It was not until 1893 that married and unmarried women were treated equally financially. Women were considered to be both physically and mentally less able than men and therefore needed to be ‘taken care of.’ The Victorian wife was expected to be devoted and submissive to her husband. She was meek and dutiful, placing her husband first and centring her life on him and their children. Above all she was pure. She was ‘the Angel in the house’, a phrase which came from the title of a poem about his wife by English poet and critic Coventry Patmore in 1854 and which gained popularity throughout the second half of the 19th Century.

This repressive image of women still grated with the writer Virginia Woolf when she wrote in 1931:

“Killing the Angel in the House was part of the occupation of a woman writer.”

For a wealthy woman of Minnie’s social status, the usual means of providing some protection of a proportion of the woman’s wealth was by a Marriage Settlement which was explained in ‘A Guide to the Unprotected in Every-day Matters relating to Property and Income’ by ‘a Banker’s Daughter’, 1864 second edition

“A Marriage Settlement – generally comprises a proportion of the lady’s fortune, and a certain proportion of the gentleman’s, which is placed in the hands of trustees, to secure a certain income for the lady and her children, in case of her husband’s death or bankruptcy. No prudent woman should marry without this provision, as, if it is made before her marriage, however much in debt her husband may become, from extravagance or misfortune, her settlement money cannot be made liable. The friends of the lady should insist upon a proper marriage settlement to the satisfaction of her Lawyer being signed before the marriage. On her return from church, the husband’s will should also be signed. It would not be valid if signed before marriage.”

Minnie’s Marriage Settlement was signed before the wedding, with her brother, Thomas Horrocks Miller as trustee.

Minnie’s life with Sutherland Dumbreck

The couple’s first child, Isabel Ellen “Nellie” was born on 4th April 1874.

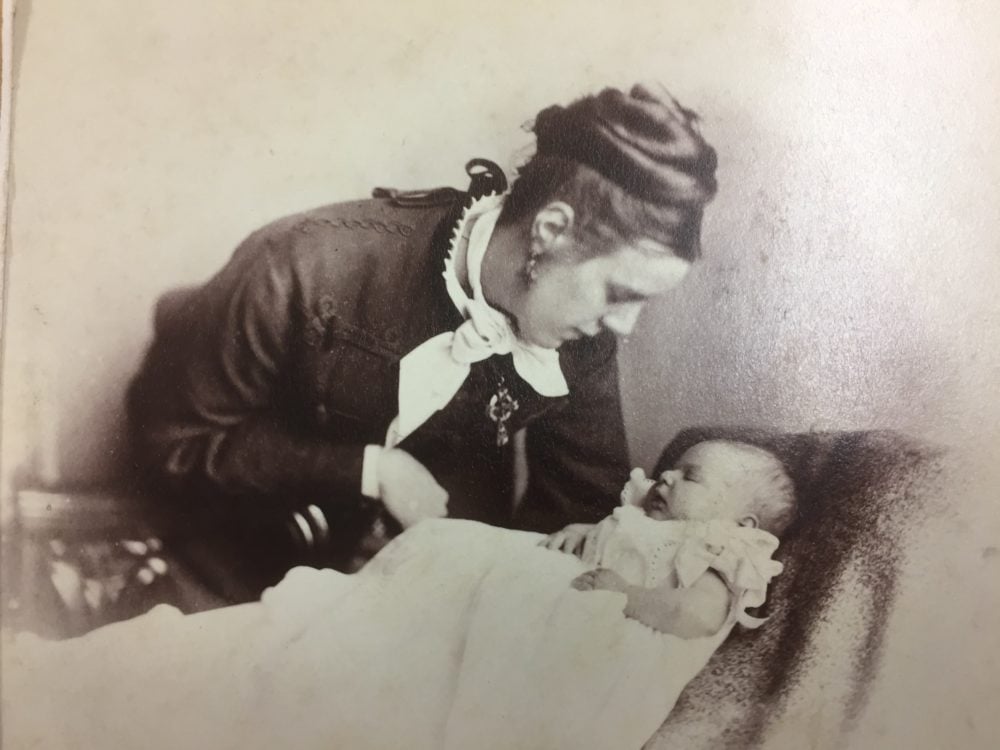

The Miller Album: Harris Museum, Art Gallery and Library

The photograph of Minnie with her first born child, Nellie, evidences the overwhelming bond of love and tenderness felt by every new mother. Sadness followed when their second child, Sutherland David Campbell born on 12th November 1875, lived for only three months and died on 16th February 1876. The couple’s family was complete with the birth of their second son Thomas Sidney on 24th May 1877.

The outward signs of domestic harmony belied the reality, however. Unfortunately for Minnie, almost from the start of the marriage, she suffered verbal, physical and emotional abuse at the hands of her young husband. The marriage faltered on for nine years until 1st November 1882, when Minnie petitioned for divorce in the High Court of Justice taking advantage of The Matrimonial Causes Act of 1857.

Minnie’s petition for a divorce on 11th November 1882 was highly unusual at that time.

Divorce proceedings were expensive and furthermore, the Act explicitly made divorce easier for men than for women: a husband could petition for divorce on the sole grounds of his wife’s adultery, whereas a wife had to prove adultery combined with other offences such as incest, cruelty, bigamy or desertion.

Minnie’s petition listed the appalling treatment that she had suffered

“Her husband was frequently drunk, habitually deserted her and committed adultery; he threatened and beat her with his belt; he dragged her out of bed by her hair, pointed a pistol at her and demanded money of her with menaces and put her in bodily fear.”

However, even with this level of mistreatment, wealthy women would rather suffer in silence or live in discreet separation from their spouse: divorce was social death for a respectable upper class woman, with the prospect of being stigmatised as a bad woman and shunned by her social circle, friends and even family. In addition, the woman risked losing custody of her children. In 1890, fewer than 2 marriages per 1000 ended in divorce.

What therefore drove Minnie to start divorce proceedings?

There is plenty of evidence from photographs and news reports that Minnie’s family supported her; the year after her divorce in 1884, she was a guest at her sister Edith’s elaborate wedding, a fact that was reported in the local paper with a comment on her dress:

“…an extremely becoming costume of pale blue gauze trimmed with embroidered net and a bonnet to match with aigrettes of gold feathers.”

The divorce petition was heard in the High Court on 24th February 1883 and the final decree nisi was granted on 13th November 1883. The children were ordered to remain in Minnie’s custody.

Minnie’s second marriage to Guthrie Hylton Jessop

Minnie’s second husband, Guthrie Hylton Jessop, was a career Army officer. He served as Deputy Assistant Commissary General with the honorary rank of Captain during the campaign in Egypt in 1882 and the Sudan campaign of 1884. He was present in the operations in Suakin and the Battle of El Teb on the 29th February 1884, for which he was decorated with the Order of the Medjidie 4th class for distinguished service before the enemy.

Egypt – Bars – El-Teb- Suakin 1884 D.A.C. Genl.G.H. Jessop C & TS

QSA – Cape Colony – Lt.Col ASC

KSA – South Africa 1901 c/02 Col.A.S.C.

Turket –Ottoman Empire –Order of the Medjidie, 4th Class.

Khedive’s Star 1882

In order to re-marry in church, Guthrie and Minnie had to submit a ‘Marriage allegation’ to the Archbishop of Canterbury in order to seek his approval. The allegation was made in person by Guthrie two days before the wedding, when he swore on oath that Minnie was free to re-marry by reason that her first marriage was legally dissolved.

The wedding took place in St. George’s Church Preston on 26th November 1885 and this time, the report of the wedding in the local paper was brief.

Guthrie and Minnie lived in Brighton, Sussex for the next ten years with no reason to suppose that they were anything but happy. There was still an unresolved issue, however. Although Minnie had received a decree absolute which dissolved her first marriage, the first Marriage Settlement was still active. In November 1895, Minnie again petitioned in the High Court for a variation of the Marriage Settlement.

Why wait ten years to seek a variation?

This could be explained by the fact that Minnie’s first husband, Sutherland, re-married in January 1896 and that he would continue to enjoy the benefits of Minnie’s fortune with his new wife.

At the hearing, all parties, including her first husband and her brother, Thomas Horrocks, who was a trustee of the settlement, gave evidence to support their position but in May 1896, the High Court ruled against a variation, ordering Minnie to pay the costs out of her separate funds.

In 1898, just prior to the outbreak of the Boer War, Guthrie was recalled to Cape Town, South Africa to serve as Lt. Col. on the Staff of the Army Service Corps. Minnie and Nellie accompanied him and on 11th March 11 1902 Nellie, only daughter of Mrs. G. H. Jessop and stepdaughter of Lieut.-Colonel G. H. Jessop, Army Service Corps. was married to Charles John Steavenson (of the 8th King’s Regiment, and commanding 11th Battalion of Mounted Infantry), third son of the Rev. Robert Steavenson, Vicar of Wroxeter, Shrewsbury.

Back row L to R: Guthrie Hylton Jessop, Charles Steavenson (groom), Sidney Dumbreck (Minnie’s son)

Front row L to R: ‘Tiny’ Fair (bridesmaid), Nellie Dumbreck (Minnie’s daughter, the bride), unknown (possibly the chaplain?), Minnie Jessop

The Miller Album: Harris Museum, Art Gallery and LibraryJust eight months after Nellie’s wedding, Guthrie died in Cape Town as a result of a carriage accident just after the cessation of hostilities on 5th November 1902.

Henrietta Mary Jessop, a brave and determined woman, lived on in widowhood for a further 24 years and died on 18th December 1926 at the home of her daughter.

It was not until the Matrimonial Causes Act 1923 that a higher degree of gender equality obtained, by making adultery by either husband or wife the only ground for divorce.

Useful Sources

See the Useful weblinks page of this website

Richard Dumbreck’s Singleton Trust Mark

The Millers Tale: by Jerry Park

By Susan Douglass