Ellen Cross

1783 - 1849 | 7, 11 Winckley Street

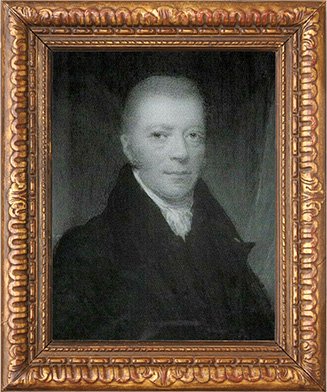

Ellen Cross was a remarkable woman. She was widowed at the age of 44 with six children, the eldest being 11. She had been married for 14 years to William Cross, an attorney and Deputy Prothonotary.

When Ellen inherited her husband’s estate she became responsible for dealing with his property and business affairs, the continued development of Winckley Square, the running of the Red Scar estate and making decisions about the education and development of their children.

Thomas Winckley had died in 1794 leaving the bulk of his estate to Frances Winckley, his six year old daughter. William Cross bought ‘Town End Field’ from Geoffrey Hornby, guardian of Frances Winckley, in 1796. William thought the land ideal to create a magnificent Georgian square similar to those he had seen in London.

William built the first house in 1799 on what was to become Winckley Square. When William died in 1827 at the age of 56 it became Ellen’s role to fulfil her husband’s plan of creating a Georgian Square which was then on the edge of the town.

Ellen’s early life in Liverpool

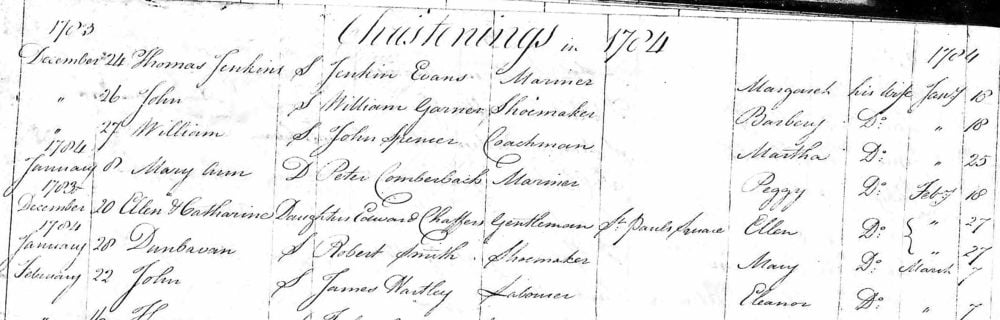

Ellen Chaffers was born in 1783. The parish registers for St Paul’s in Liverpool show that twin daughters, Ellen and Catherine Chaffers, were born to an Edward Chaffers of St Paul’s Square and his wife, Ellen (née Molyneux) on 20 December 1783 and baptised on 27 February 1784. The girls were two of five daughters born to Edward and Ellen. Ann, the eldest born in 1782 died in 1884. Their fourth daughter was called Anne born in 1785 and the youngest Margaret born in 1788.

It appears that Ellen and her sisters had a privileged and comfortable life. Edward Chaffers manufactured glass and pottery and ‘some slaving’. (Liverpool Chamber of Commerce 1774-96, members). He died in 1810, prior to Ellen’s marriage to William. His will, which was proved at Chester on 23 August 1810, is in Lancashire Archives. It names Ellen’s other three sisters as Margaret, Catherine and Ann and shows that, as well as income from investments, each daughter is left the then substantial sum of £3,000 the equivalent of £301,000 today. His will also bequeaths part of his estate to his friend Samuel Staniforth, who was a merchant and politician and along with his father Thomas Staniforth were both English slave-traders. ( Unusually, Edward’s will also appears to have been proved at Canterbury in the December of 1810)

Ellen lived in an environment that provided stimulation and encouraged her intellectual and social development. The History of Everton, by Robert Syers, 1830, provides an insightful glimpse into the family circumstances. It records that a property in Everton village once owned by a Mrs Bennett had passed into the ownership of Edward Chaffers after her death. Edward is described as:

‘….once a highly respected merchant of Liverpool; who, in his latter days, lived at this place as a retired gentleman, well-known and remembered for his cheerful, sociable qualities, and agreeable conversational powers’.

The Misses Chaffers (presumably Ellen Cross’ sisters) were still living on this site after their father’s death. However, they resided in a new building which they themselves had instigated. Syers describes it as: ‘perfectly unique in Everton’ and ‘on the whole displays a taste superior to the common usages of modern art’. He goes on to say that it could be considered beautiful were it not ‘conventual in appearance’.

Syers may not quite know what to make of the house but it speaks volumes of Ellen’s background that her sisters were confident and independent enough to set about building their own property, to their own tastes. Syers unreservedly praises the sisters as being endowed with ‘..content, happiness and independence’. Their gender seems no bar to his high estimation of their ‘mental attainments, and respectability of station and character’ which place them ‘with the first classes of Everton’s refined community’.

So, as a girl and young woman, Ellen Chaffers would have been part of the established élite within Liverpool society. It seems likely that she would have been confident and well able to hold her own in the social circles in which the family moved. There was also considerable financial security which no doubt would have bolstered that confidence and sense of belonging within the more privileged ranks of the merchant classes.

This background no doubt made her the confident and capable woman she was shown to be later in life when she became a widow.

Ellen marries William Cross 1813

Although we do not know how Ellen met William it is clear that, whilst they were not nobility or gentry, they both came from privileged and moneyed backgrounds. As such it would not be surprising for the Lancashire families of the Chaffers and Crosses to move in the same circles.

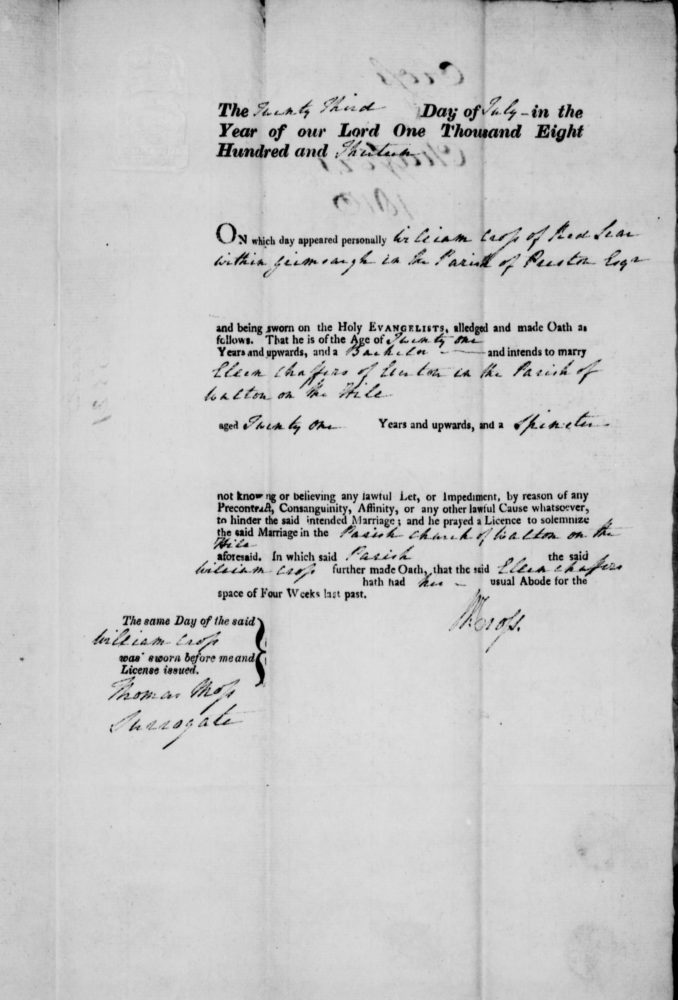

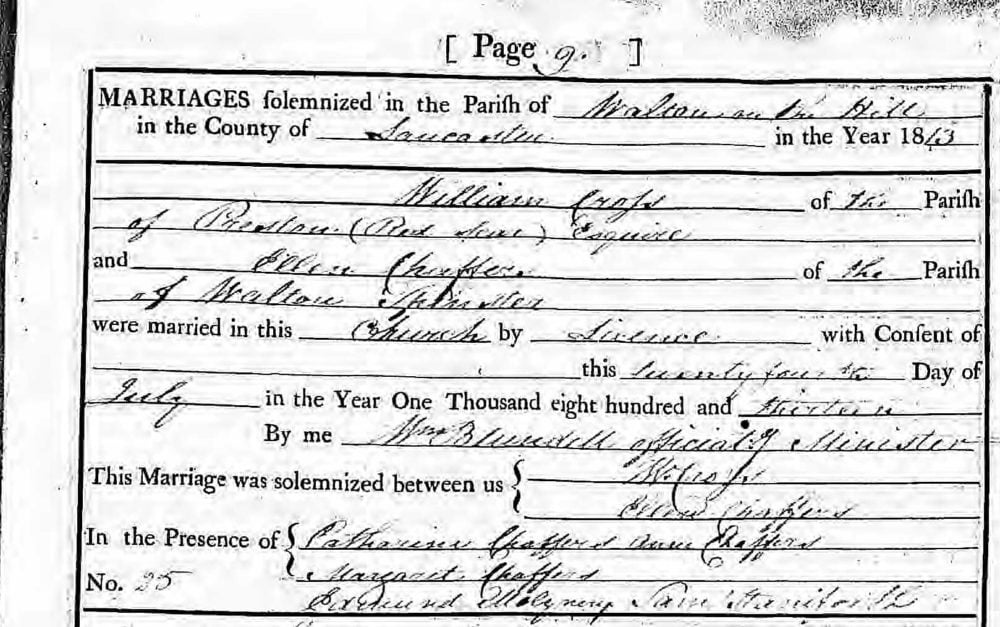

At the time of their marriage William was 42 and Ellen almost 30 so, for the period, they married quite late. They were married by licence, often an indicator of high social status, and the parish registers of Walton-on-the-Hill, show that the marriage was solemnised on 24 July 1813 with Ellen’s three sisters acting as witnesses along with an Edward Molyneux. According to Joan Perkin:

‘marriage by licence was the resort of the upper classes, who married that way to avoid their business being publicized by all and sundry’.

Family Life at Red Scar House

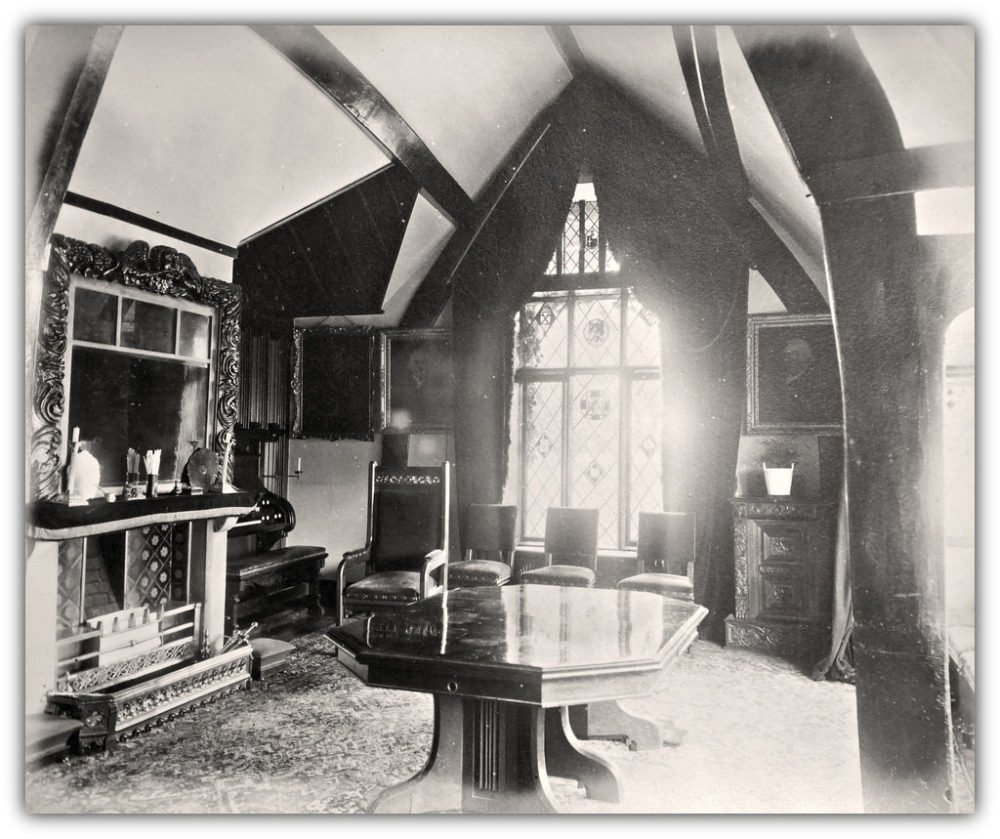

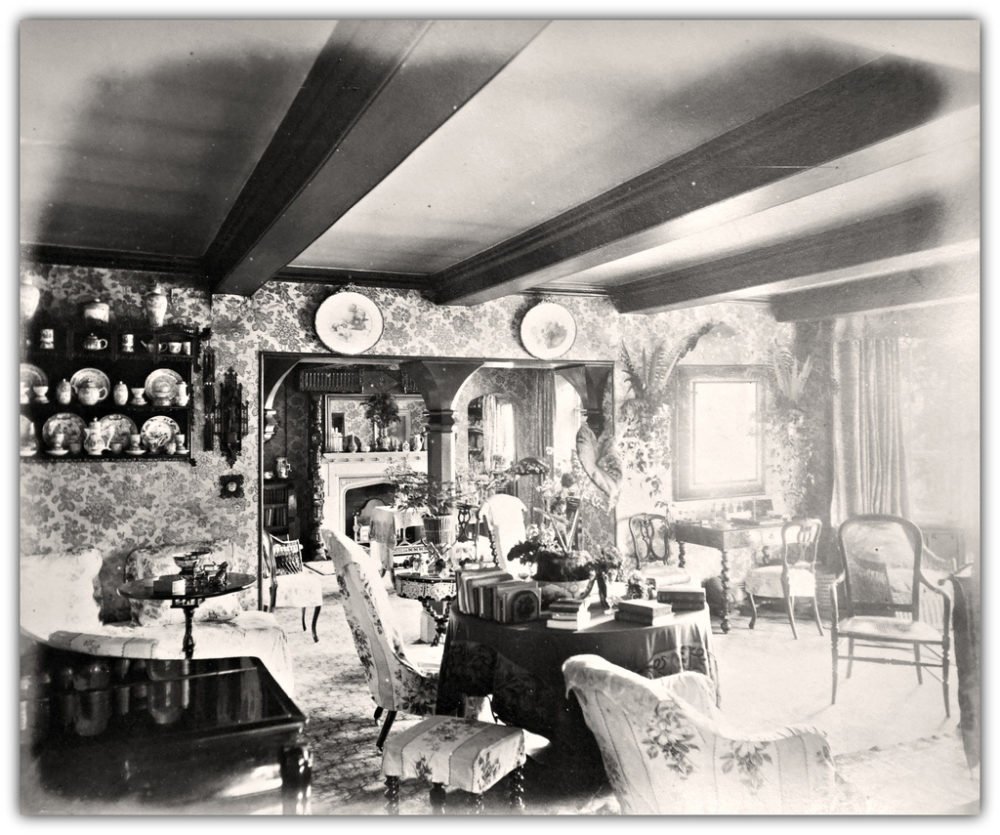

Before marrying Ellen, William had bought Red Scar Cottage, close to Grimsargh near Preston. Initially it was a weekend retreat but, after the marriage, it was enlarged to become what Marian Roberts describes as ‘an Elizabethan-type house of considerable dimensions’.

Family Life

It is evident that Ellen’s family life with William was happy and stable. William was something of a versifier and, in the Marian Roberts’ Collection at Lancashire Archives, there is a ‘Summary of the letters of William Cross Deposited in the British Library by his son, Richard Assheton, Viscount Cross’. Within this appears a copy of a poem written to his son William Asheton Cross on 19 May 1825, his 7th birthday. It reveals something of his own playful nature as well as his love for his wife and family and he advises William about the life ahead of him:

As he advances on in life

How to engage and choose a wife,

And may he meet when such his want is

One like Mama, or one of Aunties.’

One of William’s letters to Ellen in the same folder is dated 20 April 1827. It reveals the depth of affection for Ellen and the value he placed on his family:

‘…please God I hope and trust on Monday to visit my dear wife and children at home to find as I always have done my most delightful Earthly happiness there’.

This letter was written in the same year as his death and a copy of a letter from Samuel Staniforth, a family friend, probably introduced through the Chaffers family, dates from the time of his last illness. Dated 21 to 27 June it is written to Mrs T Lyons of Appleton Hall (See below; Richard Cross later married the daughter of Thomas Lyons) and relates William’s final hours. He describes William as ‘one who had attained all the perfection that I believe is permitted to human nature’ and that, in Ellen’s conduct and attendance on her husband, she displayed ‘more right mindedness’ than he had witnessed before.

These letters and other documentation reveal the close family bonds and mutual support within the family and its circle of friends. This no doubt helped Ellen and William’s children establish themselves and lead successful lives in their various chosen spheres.

Life after William’s death

Ellen and William had a very happy life together following their marriage in 1813. Sadly in 1827 at the age of 56 he caught a chill and his lungs became inflamed. It was medical practice then to ‘bleed’ the patient. Bloodletting is the withdrawal of blood to cure illness and, according to Roberts, William, ‘literally bled to death’, having been treated using leeches.

William’s death inevitably had a great impact on Ellen and all the family. However, it also opened up a new chapter in Ellen’s life as a woman of some independence and influence. William’s will, which was proved on 12 November 1827, left Ellen and others in trust all his property and shares in the Lancaster Canal Navigation. In addition, and more pertinently to Winckley Square, Ellen also received in trust the residue of premises in Preston.

Ellen never remarried after William’s death and as such, the property, affairs and money which were passed over to her control never came into the possession of a second husband. (N.B it wasn’t until 1893 that married women had the same rights as single women). Consequently, as a single woman, Ellen had a great impact on the subsequent development of the Square. The documents in Marian Roberts’ Collection show that the conveyances relating to William’s property state Ellen Cross first before other trustees. And, as Marian Roberts outlines, it was Ellen and the trustees ‘who negotiated all the subsequent sales of plots of land in the Square imposing the more specific and stringent conditions upon the purchasers’.

Another typed document in the Collection details typical restrictions relating to the Cross conveyances:

‘No Factory, Steam Engine, Lime Kiln, Gas Works, Bakehouse, Smiths or Furness, Shop, Livery or Public Stable, Inn or Public House, Coalyard…or other noisome or offensive building, object or thing shall be erected or placed upon any part of the premises.’

(N.B. Punctuation, which would not appear in the legal document, has been added)

Marian Roberts also relates the purchase of land by Isaac Wilcockson, owner of the Preston Chronicle, on Camden Place near the Square. If any of the conditions were breached this would result in Ellen applying

‘…to the High Court of Chancery for the County Palatine of Lancaster for any injunction to restrain or reform such a breach’.

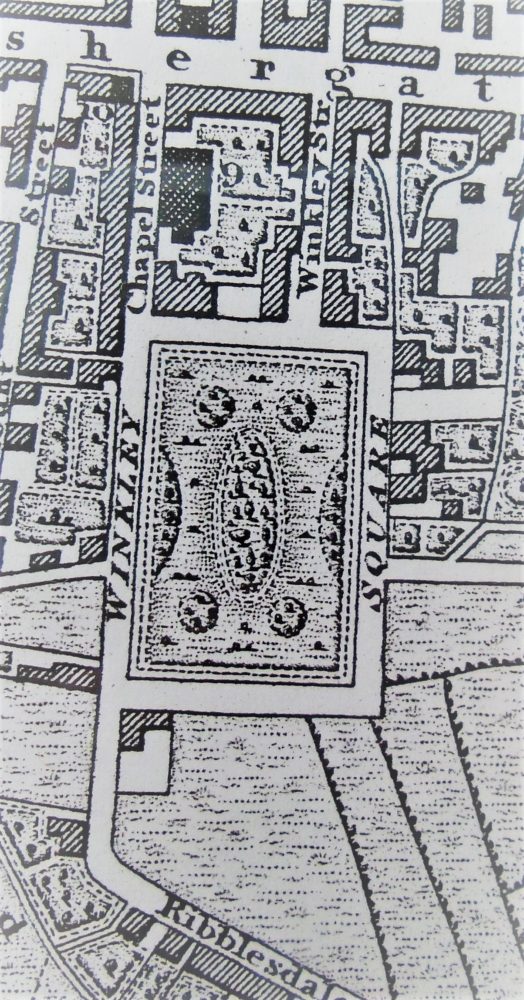

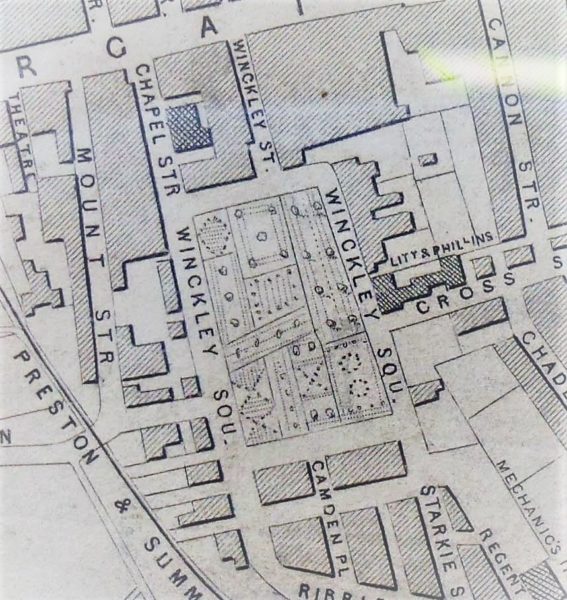

The maps show the state of Winckley Square prior to William Cross’ death in 1827 and a few years after the death of Ellen Cross in 1849.

The 1824 map shows that only a few of the houses were built around the Square. The central garden is probably an artist’s impression of a communal garden. By 1852 almost all the houses on the Square were built and the houses had separate gardens laid out as ornamental gardens.

David Hindle records details of a ‘A Family Manuscript: The Evocative Writings of Katherine Ellen Cross’. Katherine was the daughter of William Assheton and Katherine Cross and the granddaughter of Ellen and William. In the manuscript Katherine Ellen notes:

“It would seem that my Grandma Ellen Cross was more than capable of keeping an eye on her tenants’……..She must have had a pleasant way of doing it, as there is no doubt she was very much loved by all who recollected her there.”

Unlike Helen, Richard Assheton Cross did not recognise the abilities of his mother. Following the death of William, Ellen ran the estate, managed the Winckley Square development and reared the children. Richard was 4 years old when his father died but despite the significant input Ellen made in taking over where William left off, it was his father’s life – the public face of the family – that he considered of most significance and as the guiding narrative. He wrote in ‘Sketch on my Father’s Life’

.”.She felt that the best way in which she could show her love and reverence for her husband was in educating his children. ‘Devotion to those children’ will fully describe the remainder of her life. To her & to my aunts we all owe a lasting debt of gratitude. – She was allowed to live to accomplish her task. And no sooner was that over than she was called to rest”.

And what of the children?

When William died the six children ranged in ages from 6 months to 11 years. William’s will stated that Ellen was to be responsible for the education of the children. It was at Red Scar that their six children were raised and it is worth examining some of the details of their lives as far as we know them:

Ellen Dorothea Cross, born on 15 March 1816, married William Hornby in 1837 and the couple had two sons, William Hugh Hornby and Joseph Starky Hornby. Both sons were born in Garstang, but Ellen Dorothea died at the young age of 23 in London in 1840. On baptismal and census records Ellen’s husband’s profession is given as ‘clerk’. He later remarried and had more children, becoming a Vicar in Upper Rawcliffe. (Anglican clergy were described as ‘clerks in holy orders’ or simply as ‘clerks’.)

Ann Harriet Cross was born on 5 Jun 1817. The Bishop’s Transcripts of the Preston Burials also record Ann Harriet dying aged 17 and being buried in Grimsargh on 29 July 1834.

William Assheton Cross was born on 19 May 1818 and died in Preston in 1883. William became head of the family home following the death of his mother Ellen in 1849. The 1871 Census, for example, finds him as a ‘Magistrate and Landowner’ living at Red Scar with his wife Katherine and six daughters. In the 1881 Census he is a widower, living at Red Scar with a son, three daughters and ten staff working in the property. One of his occupations is given as Honorary Colonel of the Militia. In contemporary accounts he is often referred to as ‘Colonel Cross’.

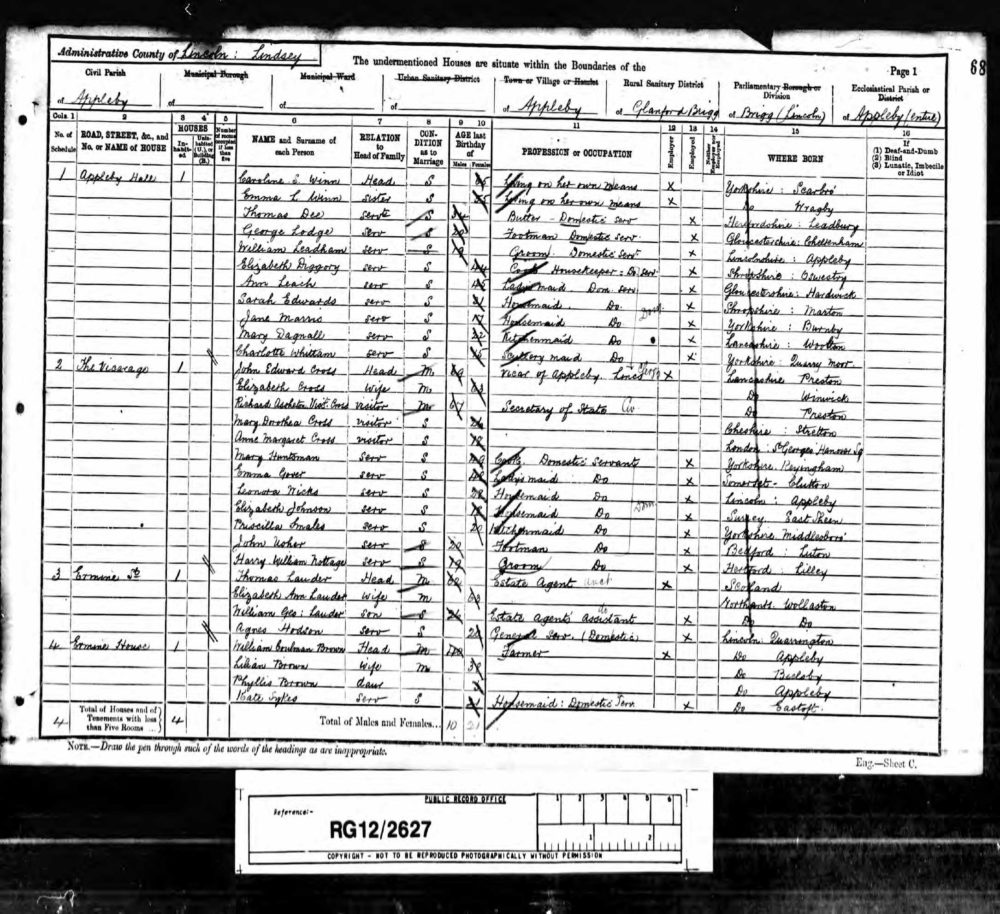

John Edward Cross, born in 1821 and baptised on 15 April of that year, had a life as a church of England minister. In the 1851 Census he is listed as the curate of Appleby in Lincolnshire. In 1854 he married an Elizabeth Hornby (perhaps some relation of his sister’s husband) in Westbourne, Sussex. Forty years later, in the 1891 census, he is shown as the Vicar of Appleby and must have had a significant income as there were seven staff to run the household. His younger brother, Richard Assheton, Viscount Cross is listed as a visitor with his occupation given as ‘Secretary of State’. John Edward died in Scarborough 8 years later in 1897 at the age of 76. A history of Grimsargh Church notes that he ‘was responsible for building the chancel and north aisle in 1840 and in 1868 re-built the nave and tower’.

John Edward and Richard Assheton Cross in the 1891 Census, Appleby

The History of Grimsargh Church

Richard Assheton Cross was born on 30 May 1823. His life is well documented and, as we have seen in the 1891 census, he was then Secretary of State and a Viscount. He has his own entry in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography which tells us of his marriage to Georgiana Lyons, a daughter of Thomas Lyons of Appleton Hall near Warrington, in 1852. They went on to have four sons and three daughters. He entered parliament in 1857 as a Conservative MP for Preston and subsequently for South West Lancashire. Later an ‘unqualified success’ as Home Secretary and had a distinguished political career. The 1911 Census gives him as ‘Privy Councillor’. At this time he was living in Hanover Square, London as a widower with a daughter and two of his granddaughters in the household, along with eight staff. He died in January 1914 at the family home in Broughton-in-Furness. One interesting aspect of the Dictionary’s entry is that it cites that he is related to Richard Chaffers, a well-known potter and William Chaffers an authority on hallmarks. Presumably there is a family connection on his mother’s side. Chaffers’ books on hallmarks are still used as authoritative sources.

Henry Assheton Cross was born in 1826 and baptised in Grimsargh on 16 November of that year. He attended Oxford University but died unmarried in his mid-twenties in 1851. He appears at the family home at Red Scar in the 1851 Census and his occupation is given as ‘Student of Medicine’. He died in the November of that year.

We can infer from the success of the male children in the church, as a magistrate and as a high-ranking government minister that Ellen was very successful in the way she met William’s wishes in educating their children. It is also clear that her personality and extended family also had a considerable impact on the family group. In her manuscript, Granddaughter, Katherine Ellen notes:

‘Our grandmother must have been a very loveable character. My father and uncles were all devoted to her and she was very clever and wise also. She brought up her children carefully and well, a widow with six children, none of them nearly grown up. She must have had an anxious life but was greatly helped by her sisters, the Everton aunts.’

Ellen’s death

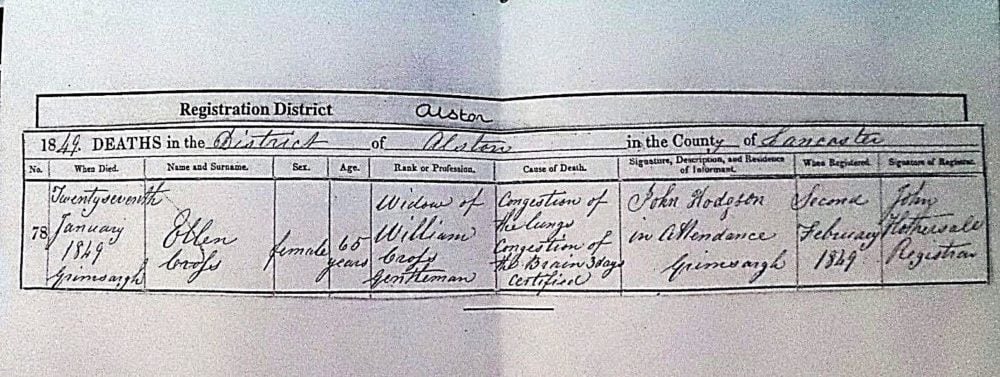

Ellen died in Grimsargh on the 27 January 1849 at the age of 65. Both her daughters, Ellen and Ann, died before her.

Ellen’s death certificate records her as the ‘Widow of William Cross, Gentleman’. Causes of death were given as congestion of the lungs and brain and the death was reported by a John Hodgson of Grimsargh. She was buried alongside her husband in the chancel of Grimsargh Saint Michael’s Parish Church.

National Archives

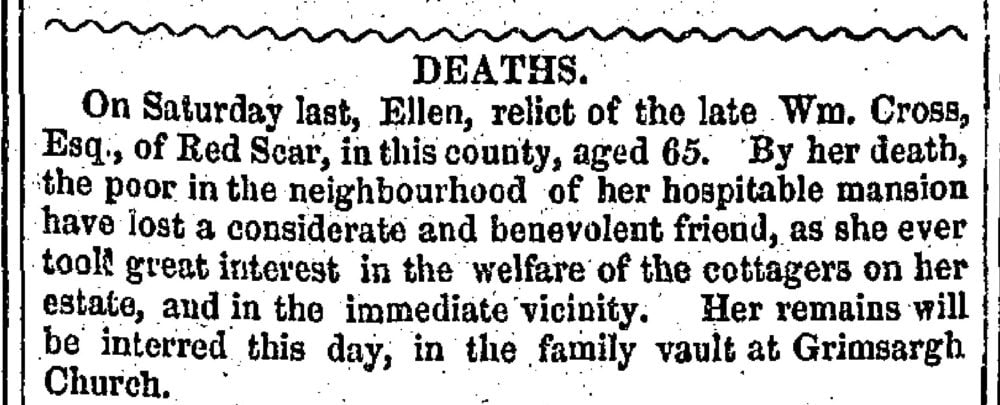

The Preston Chronicle carried a death notice on 3 February 1849. Although it is only a few lines it establishes her charitable and almost matriarchal nature in relation to her local neighbourhood:

‘By her death the poor in the neighbourhood of her hospitable mansion have lost a considerate and benevolent friend, as she ever took great interest in the welfare of the cottagers on her estate and in the vicinity’.

In spite of the limitations on the roles that women could play in the early 19th Century, Ellen had an interesting and diverse life and had significant influence on the world of business and property development in Preston. The confidence she would have needed to live and work in this way probably stemmed from her upbringing in a family of significant social standing and wealth.

Finally, and perhaps most significantly, she was a person who was much loved and valued by her husband and children. Following William’s death she was the fulcrum of family life, directing the children’s development and education as they began to develop their own lives in positions of influence within their own localities and in the national arena.

What of Red Scar House?

Red Scar House remained under the ownership of various generations of the Cross family until 1936. The last remaining owner of the house, Katharine (Kitty) Mary Cross, sold the Red Scar land to the Courtaulds Company and made the condition that they would also buy the house with it, to which they agreed. The house remained empty for many years which resulted in its complete dilapidation and eventual demolition in the late 1940s to make way for the new Courtaulds factory.

Useful Sources

This text was prepared using the online sources Ancestry, Find My Past, British Library Newspapers and The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography which are available through Lancashire Libraries and Lancashire Archives

Marian Roberts’ The Story of Winckley Square, which is available through Lancashire Libraries, was a key resource as was The Marian Roberts Collection at Lancashire Archives.

Robert Syers’ History of Everton and Ramsay Muir’s History of Liverpool are available online. Muir’s work is also at Lancashire Archives and available through Lancashire Libraries

David Hindle’s Life in Victorian Preston (2014) and Grimsargh (2002) are widely available and detail the life of the Cross family in Grimsargh.

Joan Perkin: Woman and Marriage in Nineteenth-Century England (2002)

Married Women’s Property Act 1893

Brian Lewis: The Middlemost and the Milltowns: Bourgeois Culture and Politics in Early Industrial England (2001).

By Patricia Harrison & Andrew Walmsley