Edith Rigby

1872 – 1950 | 28 Winckley Square

Without doubt Edith Rigby is Preston’s most famous suffragette and a woman ahead of her time. She was an extremely brave woman to follow her beliefs and passions despite the social pressure of the day to conform to what was perceived ‘a woman’s place’. She was fiercely committed to her principles and believed passionately in equality for both social class and gender.

She had an independent spirit and dedicated most of her life to fighting for women’s rights, particularly those of working class women, who were so frequently exploited in the factories of Lancashire. She was willing to take drastic action, and whilst not everyone would necessarily agree with some of her methods, one certainly has to admire her courage and fearlessness in the face of adversity.

Edith’s Early Years

Edith Rayner was born on 18th October 1872 into relative comfort. Her father was a doctor. The family lived at 1 Pole Street, a short distance along Church Street from the Minster. It was a large three storey house at the south west corner of Pole Street’s junction with Church Street. It is still there and now – the Derby Court Hotel.

Edith was the second child of Dr Alexander Clement Rayner and his wife Mary Pilkington Rayner née Sharples. Dr. Rayner had a practice in Preston for 50 years.

Edith had an older sister Lucy, born 1871 (died 1873), followed by her younger siblings Alice and Arthur. (Dr. Arthur Rayner in 1904 founded the X-Ray Department at Preston Royal Infirmary.) In 1879 they moved into 58 Pole Street, just across the road from number 1 (no longer standing). It was here that the rest of the children were born: Herbert, Henrietta and Harold. The children loved the family holidays spent climbing in Wales, the Lake District and Scotland.

It is possibly from these early years that Edith’s love of Wales began. The family’s connection with Wales is interesting as Edith’s sister-in law Norah Melita Millington married her brother Henry Herbert Rayner in 1915. Norah was living with her family in North Wales-Conway Bay in 1911. Henry qualified as a doctor in 1901 and became a Surgeon and worked in Manchester Hospitals.

Dr Alexander Rayner’s surgery catered for working and poor families. Dr Rayner’s obituary in 1916 in the British Medical Journal describes the kind of person he was and it is easy to see his influence on Edith’s character, interests and passions. He was described as:

“….. a man of quiet, unassuming, and reserved manner, but none the less had great determination and strength of mind.”

Edith lived close to one of Preston’s poorer areas and would have seen abject poverty at first hand. Her niece Phoebe Hesketh, in her book ‘My Aunt Edith’, recalls tales of how caring and concerned the young Edith was for those less fortunate than herself. How, at the age of 11, she collected small presents for months and got up early on Christmas Day morning to give them to workers on their way to church.

Edith attended Preston High School for Girls, Winckley Square 1883-85. It was a private school on the corner of Chapel Street and Winckley Square.

Edith then went to Penrhos College, a boarding school in North Wales, 1885-90. Alice followed Edith to the same school. They both loved Wales and in later life they moved to the Conway Valley.

We don’t know if Edith was denied the opportunity or it was by choice that she was educated only until she was 18. Her father, husband and at least two of her brothers were all able to access higher education easily but this energetic and intelligent woman did not do the same.

With the exception of the University of London, other universities did not award full degrees to women at the time but there were opportunities for women to study at universities and gain certificates and other awards from the late 1870s onwards.

Elizabeth Garrett Anderson had led the way for women in medicine and set up the London school of Medicine for Women in 1874 so opportunities for women in medicine, though limited, did exist. It is interesting to note that Dr Elizabeth Garrett Anderson was part of the suffrage movement and later became more active and spent time in prison due to her activism. Millicent Garrett Fawcett, Elizabeth’s sister co-founded Newham College Cambridge as well as being a suffragist (not a suffragette).

Edith as a young woman

Around 1890, when Edith was 18, the family moved to Fulwood, but Dr Rayner still kept a surgery at Pole Street.

‘Fairview’ was situated on the corner of Victoria Road and Garstang Road. Phoebe Hesketh tells the story of Edith’s wayward brother, Harold, spraying water from a garden syringe out of the attic window onto the passengers on the top deck of the tram. This would have been a horse drawn tram turning into Victoria Road on its way to the Fulwood Barracks terminus. Park Terrace was part of the Fulwood Park Estate, established in the 1850s.

Edith was always ready to challenge the conventions of the time. She is believed to be the first woman in Preston to ride a bicycle and as a teenager was pelted with eggs and vegetables for so doing. It didn’t stop her. She later cycled to Leicester (wearing bloomers) to visit her sister according to Phoebe Hesketh. Perhaps Edith dressed like Annie Londonderry in the image – the first woman to cycle around the world (1894-95).

“I think the bicycle has done more to emancipate women than anything else in the world,”’ feminist pioneer Susan B. Anthony said in 1896. ‘It gives a woman a feeling of freedom and self-reliance. The moment she takes her seat she knows she can’t get into harm unless she gets off her bicycle, and away she goes, the picture of free, untrammelled womanhood.”

Edith certainly felt emancipated and remained unconventional throughout her life. Marriage did not remove her independent spirit.

Marriage of Charles Rigby and Edith Rayner

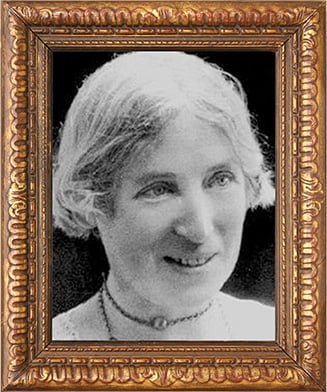

Phoebe Hesketh described Edith as tall, with ‘wheat-gold hair’ and ‘speedwell blue eyes’. She had unconventional ideas and wore dresses that looked like blue sacking with heavy amber coloured beads and her fondness for Turkish cigarettes and sandals offended many. Seemingly, she never raised her voice and gave an overwhelming impression of gentleness; yet she became a militant suffragette.

In 1893, at the age of 20 and having reportedly turned down numerous ‘suitors’, Edith married Dr. Charles Rigby, age 35. The wedding took place in the Wesleyan Methodist Chapel, Lune Street built in 1816 and remodelled in 1862-3. (Now Central Methodist Church).

The marriage, reported in the Preston Herald 9th September 1893, was an elaborate affair in a packed church. Edith was described as looking very pretty in her:

‘…..rich ivory satin duchesse trimmed with mechlin lace, and having a full court train and she wore a lace veil. She carried a choice bouquet and wore for ornaments a diamond crescent, a gift from the bridegroom.’

The paper prints the gifts the numerous guests gave the married couple including the gifts given by the servants of Dr Rayner and Dr Rigby. It is worth noting that Dr Brown, who was to become their next door neighbour when they moved to Winckley Square, and Mr and Mrs E H Booth attended. E. H. Booth & Co. Ltd was founded in June 1847 when 19-year-old tea dealer Edwin Henry Booth opened a shop called The China House in Blackpool. Read the full Transcript of the newspaper report

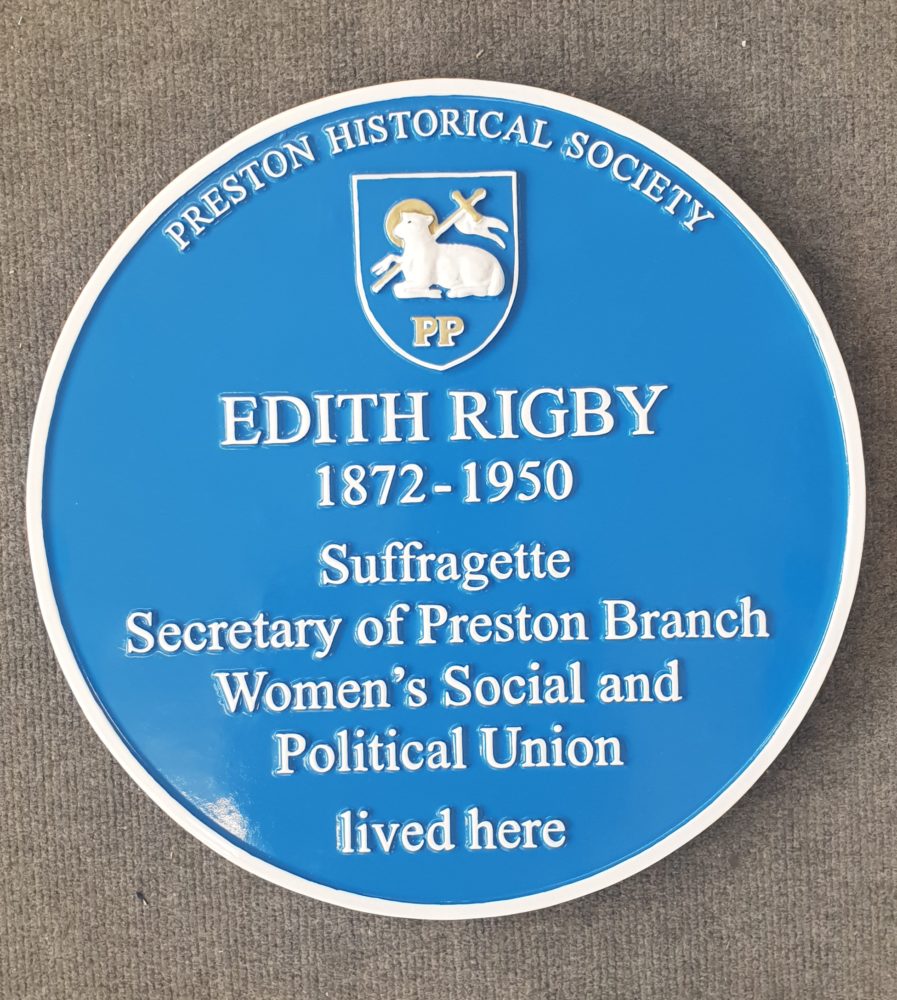

Edith and Charles (Charlie) initially lived on Ribblesdale Place before moving to 28 Winckley Square. The Blue plaque marks the home Edith shared with her husband and their son Arthur (known as Sandy) who they adopted in 1905 when he was age two. Arthur (named after Edith and Charles’ brothers) grew up in Winckley Square and attended Preston Grammar School.

The blue plaques scheme, run by English Heritage, celebrates the links between notable figures of the past and the buildings in which they lived and worked.

Edith: Social Activist

Edith scandalised local society by treating servants as equals. The Rigbys’ servants did not need to wear the standard uniform and they ate at the family dining table. Edith happily carried out menial tasks such as cleaning the step (with Sandy) much to the annoyance of her neighbours who, according to Phoebe Hesketh, told her that:

“….her appearance and behaviour, and most of all her way of treating inferiors, was a disgrace. If she couldn’t alter her ways, they implied she had better leave the neighbourhood.”

Edith organised a wide range of activities for working class girls and women. In 1899 she rented the first floor of the old St Peter’s School in Brook Street, allowing girls to meet and continue their education beyond the age of 11. Up to 40 girls attended two evenings a week. They paid ‘tuppence’ (2d- two old pence- was pronounced tuppence pre-1971). They were dressed in clogs and shawls and during the summer months would go to Moor Park to play cricket. Phoebe Hesketh’s book includes reminiscences of some of the girls who attended the club.

In 1905 Edith joined the Independent Labour Party and a year later formed a branch of the Women’s Labour League in Preston.

She took up the cause of women’s dreadful working conditions at Woods Ltd. Tobacco Manufacturers (their town centre building is still standing at the north end of Avenham Street) and helped to establish the first union for women in Preston outside the textile industry.

Edith: Women’s Suffrage

In 1904 Edith joined the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) and went to meetings at Mrs Pankhurst’s house in Manchester where she became friends with Christabel and Adela Pankhurst and Annie Kenney. Annie was an English working class suffragette who became a leading figure in the Women’s Social and Political Union

Edith became utterly committed to women’s suffrage. In January 1907 she established the Preston branch of the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU). She recruited suffragettes from the local Labour Party where she met Elizabeth Hesmondhalgh (Beth), a cotton spinner who was 22 years old. Along with Annie Kenney they coaxed Beth into joining the militant movement. Beth wrote:

“…she was so persuasive she tried to get round my husband to persuade me. Well, I joined half against my will and the next thing I knew I was asked to face imprisonment.”

Edith was the secretary and responsible for the organisation, administration and meetings of the Preston branch which were held at number 28 Winckley Square. Larger WSPU meetings were held at the Assembly Rooms.

Sunday evening meetings at number 28 were to discuss social, political and personal problems – NOT suffrage on the Sabbath. Edith would sit crossed legged on the floor, chain smoke Turkish cigarettes and listen sympathetically to ‘husband problems’.

If important WSPU members of the movement visited Preston they stayed with Edith and Charles. The members would wear their ceremonial long white dresses and sashes of white-corded ribbon, edged with purple and green.

‘Deeds not Words’

On 13th February 1907 four Preston women travelled to London to the WSPU’s first ‘Women’s Parliament’ in Caxton Hall: – Edith Rigby, Beth Hesmondhalgh, Rose Towler and Grace Alderman. Edith led the charge towards St Stephens Entrance with Rose Towler, a schoolmistress, not far behind ‘brandishing their petitions like a torch’. Edith sprained both wrists and her thumbs were bent back as she tried to fight past the police.

The meetings were held every year to coincide with the Opening of Parliament. By walking to the House of Commons they put into action the Suffragette motto ‘Deeds Not Words’. Edith, Grace, Rose and Beth along with Christabel and Sylvia Pankhurst were among the 57 women arrested that day and sent to Holloway Prison for a month. Edith wrote from prison;

“Do not these things repay one thousand fold for the painful publicity and personal suffering?”

The Lancashire Daily Post wrote about the day’s events. The Editor had hoped that the prisoners:

“…..would undergo the full rigours of prison discipline……..be allowed to serve their full term without any amelioration of their conditions.”

Charles Rigby was a great supporter of Edith and the movement. He wrote many letters to the government and the local papers. He was extremely proud of his wife and responded to the Editor’s comment. Lancashire Daily Post 18th February 1907

“Sir, I believe this to be greater brutality in words than anything that has been done in deed by any suffragist now in prison. ……..For at least 10 years of the latter part of her life she (Edith) has given every day and all the day to the tasks of visiting, organising, studying the causes of distress among her sisters. No one but myself knows the hours she has worked with … singleness of purpose neither being debarred by opposition, contempt, loss of friends or any other cause, content to be misunderstood, so long as her conscience was clear that she was doing her duty. ….. A greater, truer, better hearted woman ever lived ..…. because she thinks the mothers of this country should have a voice in its management.……. Prison is her reward.” Extract from letter

The Press Reports

The Press Reports, March 1907 (Report 1, Report 2) describe how the London Excelsior Band greeted the suffragettes, including Edith, when they were released from Holloway Prison. Their crime had been to demonstrate outside the House of Commons. The press report also includes a letter Ramsay MacDonald sent to Mrs Hawkins.

They marched behind the band through London and ended up in a restaurant for a ‘Welcome Breakfast’ at ‘Eustace Miles’ vegetarian restaurant’ at Charing Cross. 300 women heard burning speeches. Edith, followed Christabel Pankhurst, and said how pleased she was to have been to prison:

“Prison is a grimy, serious institution, a new experience for many of us who have never known cold and hunger. It’s good for us all to experience conditions which are quite beyond many people’s social horizon.”

Before returning to Preston Edith spent three days in Reading where she met, by chance, 19 year old, Charlotte Mason, a trainee sanitary inspector. Meeting Edith inspired Charlotte (Charlie) to join the WSPU. In 1909 when Charlie finished her training she became a suffragette poster girl and led marches dressed in armour on a white horse (Dressed as Joan of Arc).

Edith was jailed seven times for her militant actions and during this time she took part in hunger strikes and was subjected to force-feeding

An Interview with Edith: In her own words

Edith took every opportunity to attend protest rallies. At a meeting addressed by Winston Churchill in 1909 Edith protested by throwing a black pudding. During the opening of the Suffragette campaign in Lytham, Edith was interviewed by a journalist who went under the pseudonym ‘Will -o’-the-Wisp’. He asked how Edith had become associated with the Suffragette movement. Her reply was:

“I happened to be in Liverpool at the time Miss Gawthorpe was addressing an open-air meetings at the mill gates, and I sent in my name. ……………..

Six years ago I had the usual notion that it was not a woman’s sphere…..”

Read the full interview with Edith Rigby along with an interview: Mr. Clifton and the Suffragettes, Mr Clifton hated all suffragettes- except for Mrs Rigby:

I hate Suffragettes—except one whom I like very much—but all the others, I hate them,………..

Edith was clearly inspired by Mary Gawthorpe (1881-1973) who came from a working class background and was an excellent public speaker.

Winston Churchill visits Preston

On 3rd December 1912 Winston Churchill visited Preston to talk up the People’s Budget. No vehicles or pedestrians were allowed around the Public Hall (Now 1842 Restaurant and Bar) after 4pm in the afternoon. Members of the Special Branch were sent from London to assist the Preston police. All the windows were boarded up and a tarpaulin covered the roof. There were hoses at the ready in case women did manage to get on the roof. The chief Constable warned all the nearby residents of the ‘awful consequences that would overtake them if they harboured a suffragette.’

At about midnight the night before Churchill’s visit, four suffragettes stuck posters onto the walls of the Public Hall, the Prison, the Liberal Club, post offices and pillar boxes. The poster showed a suffragette being force fed through a nasal tube. Later that day Rosamund Massy threw a stone through the General Post Office window carrying a message which said:

“Message to Mr Winston Churchill: This stone through your post office window is to remind you of your broken promises to the Suffragists of Manchester and Dundee.”

She pleaded guilty to causing £2 worth of damage and was sentenced to a month in prison. By 6pm that evening between 5000 and 6000 people were gathered outside the Public Hall. Mostly men and some women were allowed in after having their credentials checked. When Edith and her fellow suffragettes tried to enter they were bundled into a black maria and driven off.

They were sentenced to seven days in prison but Edith’s father-in-law, Dr Rigby, paid her fine; much to her annoyance. Her brother Arthur told a reporter , referring to Margaret Hewitt, a leading suffragette;

‘It’s that little painted jezebel who has led my sister astray’.

Edith was most indignant and by 6pm on 4th December was in Liverpool where Churchill was due to speak. Edith was arrested for breaking a window and sentenced to two weeks in prison where she refused food and was force fed.

Hunger strikes and force feeding

The government sought to deal with the problem of hunger striking suffragettes with the 1913 Prisoners (Temporary Discharge for Ill-Health) Act, commonly known as the Cat and Mouse Act

This Act allowed for the early release of prisoners who were so weakened by hunger striking that they were at risk of death. They were to be recalled to prison once their health was recovered, where the process would begin again.

The first person to be force fed is believed to be Mary Lee who along with three other women was sent to Winson Green Prison, Birmingham, after an action against the Prime Minister in September 1909. All refused food. Four days later, on Sunday 16 September, she was forcibly fed. She recalled what happened to her:

“On Saturday afternoon the wardress forced me onto the bed and two doctors came in. While I was held down a nasal tube was inserted. It is two yards long, with a funnel at the end; there is a glass junction in the middle to see if the liquid is passing. The end is put up the right and left nostril on alternative days. The sensation is most painful – the drums of the ears seem to be bursting and there is a horrible pain in the throat and the breast. The tube is pushed down 20 inches. I am on the bed pinned down by wardresses, one doctor holds the funnel end, and the other doctor forces the other end up the nostrils. The one holding the funnel end pours the liquid down – about a pint of milk… egg and milk is sometimes used.”

On one occasion, when the police called at number 28 Winckley Square to re-arrest Edith under the ‘Cat and Mouse’ Act, she made her escape to Ireland from the rear of the house, wearing workman’s clothes and riding a bicycle!

Boycott of 1911 Census

Nationally, the suffragette movement decided to boycott the 1911 (2nd April) census. Its slogan was: If we don’t count – we are not going to be counted.

The census listed everyone who spent census night at the property. The householder completed the census return. The boycott took place in two ways: – by spending the night away from home or ‘spoiling’ the census.

Edith’s name is not on the 1911 census. She may have been in Manchester where a large house was packed with census evaders and was renamed ‘Census Lodge’. Or she may have gone to London and joined her sisters at Wimbledon Common where they spent the night and enjoyed a picnic of roast fowl, sweetmeats and tea. Or perhaps she joined her fellow Suffragettes walking around Trafalgar Square all night.

Such overnight events happened all over the country. Punch joked:

The suffragettes have definitely taken leave of their census

Many expected to be fined or face a prison sentence but no-one was prosecuted.

Edith commits arson

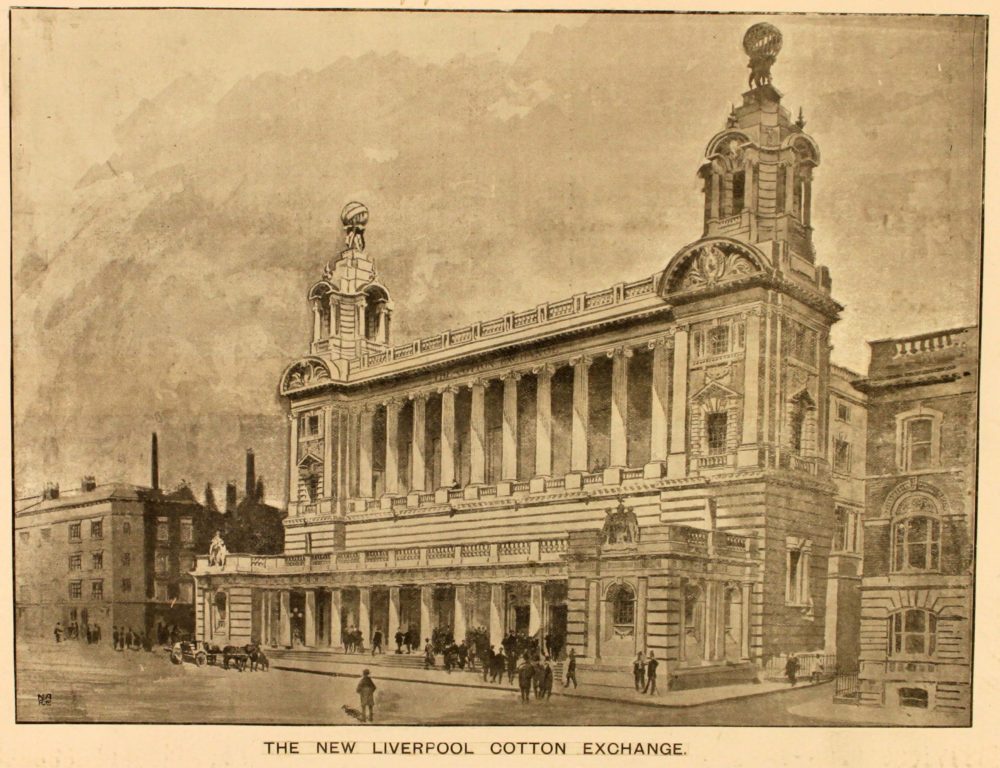

Edith’s activism included planting a bomb in the Liverpool Cotton Exchange on 5 July 1913, it was stated in court that ‘no great damage had been done by the explosion’

Her most notorious act was to firebomb Lord Leverhulme’s wooden cottage at Rivington in the early hours of 7th July 1913. She knew the cottage would be empty as Lord Leverhulme was dining with Lord Derby and the King & Queen at Knowsley. She travelled there with her accomplice, Albert Yeadon, driven by the Rigby’s chauffeur!

The attack resulted in damage costing £20,000. Afterwards she said:

“I want to ask Sir William Lever whether he thinks his property on Rivington Pike is more valuable as one of his superfluous houses occasionally opened to people, or as a beacon lighted to King and Country to see there are some intolerable grievances for women.”

Edith handed herself in at the police station and admitted to both acts and was sentenced to 9 months hard labour in prison. She was probably not responsible for the tarring of the statue of Lord Derby on Miller Park although it was possibly her idea. This was done because Lord Derby’s grandson opposed votes for women. You can read more about Edith’s arson attack on Royton Cottage on the Lancashire Past website. The Suffragette Arson Attack at Rivington, near Horwich

Formation of the Independent Women’s Social and Political Union (IWSPU)

When war broke out in 1914 Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst ordered the members of the WSPU to stop all militant action. They turned their attention to patriotism and changed the name of their newspaper from ‘The Suffragette’ to ‘Britannia’. All suffragette prisoners were released from prison.

Some members, including Edith, disagreed with the WSPU’s decision not to campaign on suffrage issues during WWI. A breakaway took place in March 1916, led by Charlotte Marsh, a former organiser for the WSPU. She founded the ‘Independent Women’s Social and Political Union’, and launched a journal, the ‘Independent Suffragette’. Other leading members included Edith Rigby, who founded the Preston branch and Dorothy Evans, who served as its provincial organiser.

An ally of the Pankhursts until the outbreak of the war, Edith supported the war effort but also continued to campaign for female suffrage.

In 1917 the IWSPU disbanded and became the Women’s Party.

Move to Marigold Cottage

After 22 years living on Winckley Square in 1915 the Rigby Family and housekeeper, Mrs Tucker, moved to Marigold Cottage, which had an orchard and 5 acres of land, at the end of Howick Cross Lane, Penwortham.

Edith was influenced by new agricultural methods, like those developed by Rudolf Steiner.

Steiner was an Austrian born philosopher, social reformer and follower of esotericism.

Edith lost no time in joining the Women’s Land Army, from this time she wore breeches and a farmer’s smock and cut her hair short. One of her first jobs was to make the premises habitable and the land productive. Edith immediately set to and painted the cottages, (marigold, what else?) cleared the land and prepared the way for bee hives.

She organised her friends into collecting and bottling fruit, making jam and generally helping the war effort. As her enterprise expanded, after lots of hard work, she drove her bay, ‘Nutty’, twice a week to sell her good produce cheaply at Preston Market. (Hesketh)

Hutton and Howick Women’s Institute

The Women’s Institute (W.I.) was formed in 1915 on Anglesey. The first branch was at Llanfairpwllgwyngyllgogerychwyrndrobwllllantysiliogogogoch. (aka Llanfair PG) The first branch in Lancashire was established by Edith in 1918 and known as Hutton and Howick Women’s Institute.

Some women get the Vote

Women played a significant role during the war years. They proved that they were more than able to do the jobs of men. The value of the women’s contribution to the war effort combined with the dread of suffragette activism continuing and probably escalating contributed to the passing of the Representation of the People Act 1918 which passed into law on 6th February. The act gave the vote to women who:

- were 30 years and above,

- were graduates.

- owned or rented property at least £5 annual rental or were married to someone who did.

The Act also gave the vote to all men over 21 years old; or over 19 years if they had fought in the war.

Giving women the vote was ‘scary’ for some men especially as, if they had qualified on equal terms to men, they would be the majority voters. This was not simply due to male deaths during the war years. Women were (and probably have always been) the majority of the population, as they outlive men.

The 1911 census recorded 107 females to every 100 males in England and Wales. In 1921 it was 110. This fear was one reason for the proposal to raise women’s voting age relative to that of men – 35 years was proposed by some. Another reason was that older women were believed to be more mature and stable and by restricting voting to the property owning classes it reinforced a conservative bias by excluding working class women. Following the 1918 Act women made up 43% of the voting population. It reduced some class and gender inequalities but reinforced others. Women carried on fighting for equal voting rights and, tired of evasions, threatened to reinstate militant action. In 1928 women gained the vote on equal terms with men and became 53% of the electorate. The Daily Mail warned ‘It may bring down the British Empire in ruins’ Clearly it did not but the 1929 election reinforced the Daily Mail’s fears by returning Labour as the largest party for the first time.

Edith’s move to Wales

Edith and Charles’ son Arthur (Sandy) married Hilda Stewart at St James’s Church, Preston in 1925. The church was on Avenham Lane and Knowsley Street. The Victorian church was demolished in the 1960s and later replaced with the current building.

By 1926 Edith and Charles were looking around Llandudno for a property to retire to. They finally decided on a property development in the village of Llanrhos, which is just south of Llandudno. It was here in July 1926, whilst Edith was checking the progress of the house that she received a message to say that Charles was very poorly. By the time Edith arrived back at Marigold Cottage, Charles had passed away at the age of 68. He died of pneumonia after only a few days illness. Charles’ estate was £6,624 which converts to approx. £400K today.

Edith, a widow at the age of 54, moved into ‘Erdmut’ St Anne’s Gardens, Llanrhos at the end of 1926, her unmarried younger sister, Alice, moved into the adjoining semi ’Mount Grace’.

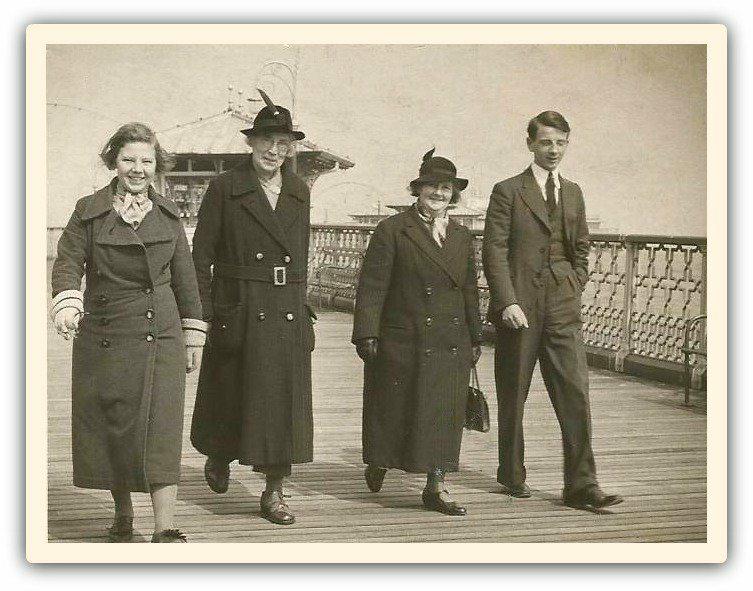

A family that visited on a regular basis were the Higginsons. Eleanor Beatrice Higginson was a fellow suffragette and along with her daughter Edith and her son Richard they were captured promenading along Llandudno Pier in 1936.

In 1939 Edith was sharing her home with her companion Helen Ford-Tucker, age 50 years and Emily Crockart an artist, age 54 years. Alice lived alone next door.

Edith crosses the Atlantic

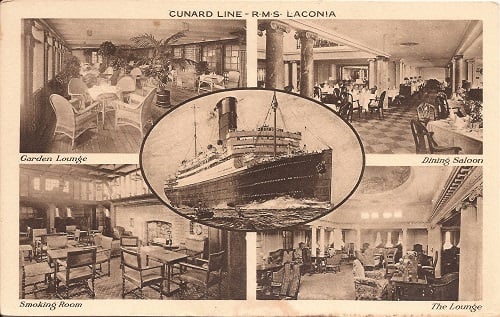

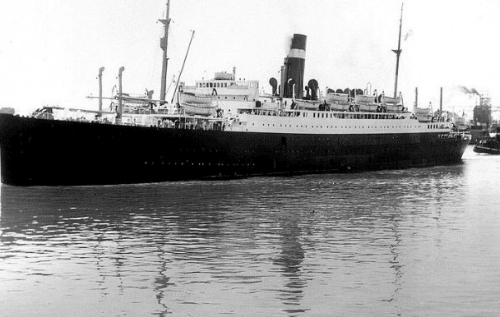

Edith never lost her spirit of adventure. At the age of 67, three years after the photograph on the pier was taken, she went to North America for over 2 months with her niece Margaret Rayner, who lived with her father Arthur in Garstang, Preston. They travelled in style, leaving for New York 26th May 1939 and sailing on the Laconia, which was clearly a very comfortable ship for passengers.

They returned from Montreal, Canada on 1st August 1939 on the Athenia. One month later, on the 3rd September, Britain and France declared war on Germany and just eight hours later a German torpedo struck the SS Athenia passenger liner, 200 miles north west of the Hebrides. It sank in 14 hours. Of the 1418 passengers and crew on board 117 were lost. The Athenia was the first ship to be sunk in WW2.

Margaret served in the Admiralty Aid Detachment Nursing Service during the war.

Edith dies 1950

In later life Edith developed Parkinson’s disease but it didn’t stop her doing early morning sea bathing. By 1950 she was becoming very frail and had a fall, which resulted in a broken thigh. This and other long standing kidney problems resulted in her death on 23rd July 1950. She died in her own bed with her sister Alice by her side. At her own request she was cremated at Birkenhead Crematorium and her ashes were scattered on her husband’s grave in Preston Cemetery.

Useful sources

See the Useful weblinks page of this website

This content is based on sources including ‘My Aunt Edith’ written by Edith’s niece Phoebe Hesketh,

Recent original research by Peter Wilkinson, one of the Friends of Winckley Square

Recent publications: History Today May 2018 Vol 68 Issue 5 ‘Votes for All’ Pat Thane,

Hearts and Minds Jane Robinson, Doubleday Pub. 2018

Rise up Women Diane Atkinson, Bloomsbury Pub. 2018

Edith’s Birth Certificate

Edith’s and Charles’ Marriage Certificate

Edith’s’ Death Certificate

By Patricia Harrison & Peter Wilkinson