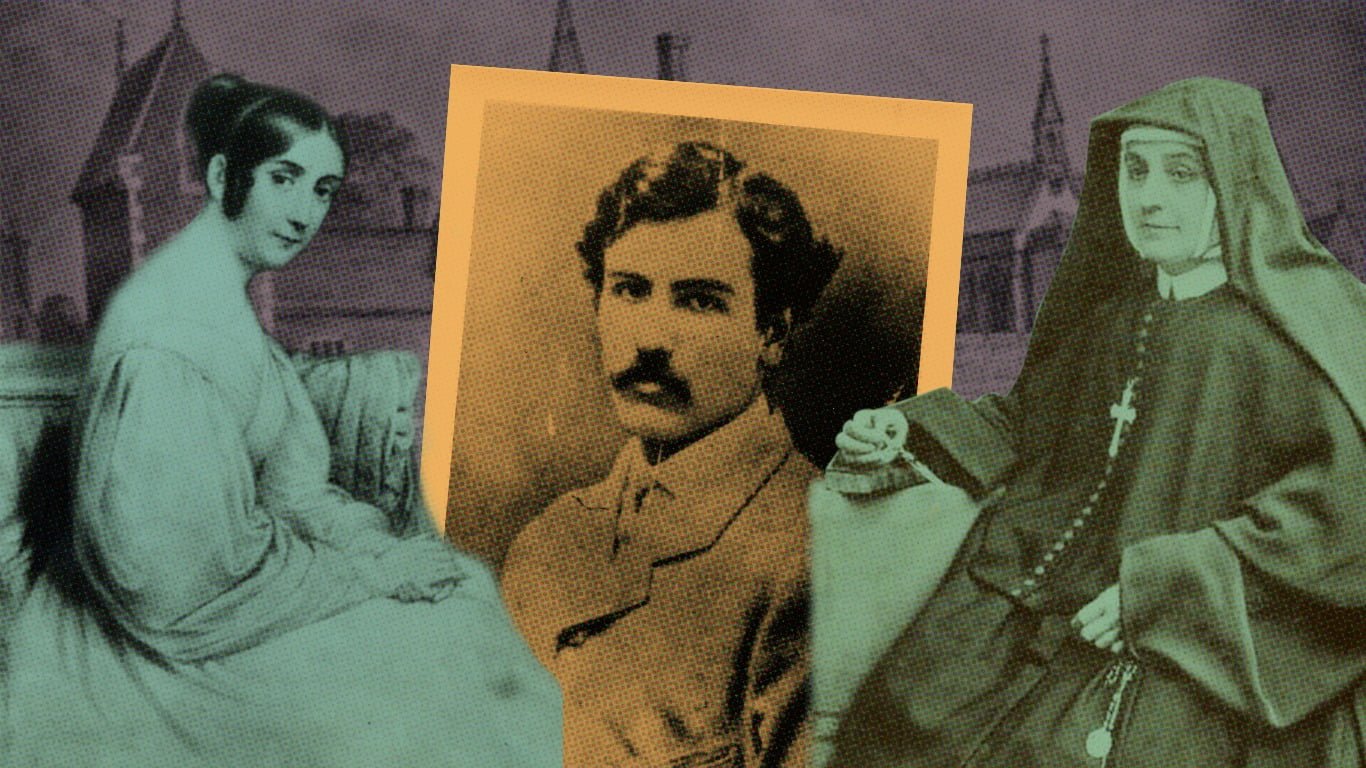

Cornelia Connelly

1809 – 1879 | 22 & 23 Winckley Square

A wife, the mother of five children and a nun who founded the religious order ‘The Society of Holy Child Jesus’. A truly remarkable woman who had a significant impact on education in Preston.

Cornelia Connelly, née Cornelia Augusta Peacock, was born in 1809 in Philadelphia. She died in 1879 in St. Leonards in Sussex. Cornelia was the subject of an acrimonious ecclesiastical controversy. Her motto was ‘Actions not words’ which seems to be the mantra by which she led her life.

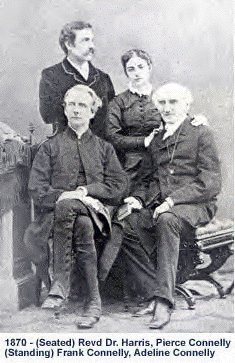

Preston Digital Archive, Linda Barton

Early Beginnings 1809

Cornelia Peacock was the youngest child of a large family. We know that her father died when she was nine. Cornelia was brought up initially as a Presbyterian. By the age of 14 she had lost both parents and was living with her half-sister, Isabella, and Isabella’s husband, Austin Montgomery. Austin was an Episcopalian (The Anglican Church in USA).

Youth in Philadelphia 1820

Cornelia had been well educated by tutors at home. She was an attractive, well-educated woman with a lively personality who was described as being intelligent, happy, strong-minded, hot-tempered and untidy.

The Philadelphia of Cornelia’s youth was a vibrant city: the Declaration of Independence had been signed there just over thirty years earlier.

Cornelia reflected the spirit of her native city and, all her life, was independent, creative and courageous.

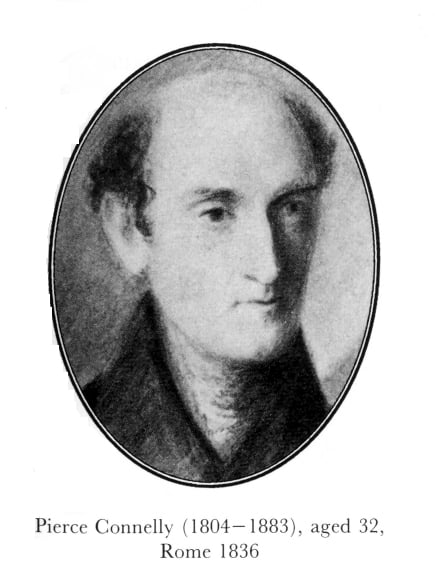

Marriage to Pierce Connelly 1831

(age 23) Artist unknown: SHCJ website

In 1831 Cornelia was baptised into the Protestant Episcopalian Church . In December she married the Reverend Pierce Connelly, an Episcopalian minister, despite her family’s objections. Pierce was five years her senior and a graduate of the University of Pennsylvania but he was deemed socially inferior by Isabella. There were mixed reactions amongst her relatives but Cornelia and Pierce, by all accounts, had a very happy relationship.

The two moved to Natchez, Mississippi, where Pierce had accepted the rectorship of the Holy Trinity Episcopal Church. They were a happy couple and welcomed by their parishioners. Pierce profited from land investments and in 1835 was appointed chairman of the Episcopal Convention of the Southwest, which augured well for a future bishopric.

Home and Children 1835

They lived for three years at White Cottage where their first two children, Mercer (a boy) and Adeline, were born.

In 1835 a wave of anti-Catholic resentment struck the US following large scale Catholic immigration from Europe. The Connellys delved into a study of Roman Catholic beliefs and practices. Pierce became uncertain in his own beliefs and in August 1835 he resigned his post in order to explore the claims of the Roman Catholic Church and went to St. Louis to consult with Bishop Joseph Rosati about conversion. For both Pierce and Cornelia, religion held a place of importance; they were young believers who searched for answers to the most serious questions of their lives.

In resigning, Pierce sacrificed a promising career as well as the financial security of his family. Cornelia supported him fully:

‘I am ready to submit to whatever he believes to be the path of duty.’

Journey to Rome

Pierce took his family to Rome before committing himself. Cornelia however, had already been received into the Catholic Church in St. Louis Cathedral in New Orleans; whilst waiting for passage to Italy. They sailed in December 1835

In Rome, Pierce petitioned for admittance to the church so compellingly that, after meeting Pierce in a personal audience, Pope Gregory XVI is reported to have been moved to tears. Two months later Pierce was received into the church.

Ordination was a different matter. Celibacy was required of priests in the church’s Latin rite. Vatican officials suggested that he consider instead the Eastern rite– which ordains married men – particularly as Cornelia was pregnant again. Pierce ignored the advice. He had ambitions to become a bishop. There were no Eastern-rite parishes in the US for him to serve, and only celibates can become Eastern-rite bishops.

The family were otherwise happy in Rome, where they stayed in the palazzo of the English Catholic, John Talbot, Earl of Shrewsbury. The Connellys moved on to Vienna, where their 3rd child John Henry was born.

Teaching at the Sacred Heart 1838

The banking crisis in 1837 in the US forced Pierce to return to Natchez to find employment. In the spring of 1838 the Connellys accepted an invitation to live and work at Grand Coteau, a remote Louisiana outpost. Pierce was offered a position of English teacher at a Jesuit college in Grand Coteau. Cornelia (29) taught music at an academy for girls while raising their (by now) four children and by private tutoring. For the first time the couple were poor but apparently content.

Their faith was supported by spiritual direction, retreats, and conversation with the priests and nuns. Their spiritual lives and personal relationship endured a series of painful events. In July 1839 a daughter, Mary Magdalene, was born but died after only two months.

In early 1840, still grieving the baby’s death, their two year old son John Henry was playing with his Newfoundland dog, when the dog accidentally pushed him into a vat of boiling sugar. There was no doctor available, and he died of severe burns in Cornelia’s arms after 43 hours. From this anguish was born in her a life-long devotion to Mary as Mother of Sorrows.

Pierce and Cornelia separate 1844

Eight months after the death of John Henry, while making a retreat, Pierce informed Cornelia that he was now certain of his vocation as a priest in the Roman Catholic Church. Cornelia was aware that this would mean their separation for life and the breakup of their family. She urged him to consider it deeply.

The couple agreed to a period of celibacy. Cornelia was already pregnant with their fifth child, Pierce Francis (Frank), who was born in the spring of 1841.

In 1842, Pierce broke up the family. He sold their home and went to England, where he placed Mercer, age 9, in a boarding school. He applied unsuccessfully to join the Jesuits.

Cornelia stayed with the two younger children in a small cottage in the convent grounds at Grand Coteau, leading a nun-like life of work and prayer. In 1843, Pierce arrived in Rome, where Pope Gregory instructed him to bring his family so that officials could discuss the matter with Cornelia.

Pierce returned to the US and took his family with him back to Rome. They settled into a large apartment near the Palazzo Borghese. After receiving Cornelia’s personal consent to her husband’s ordination, the Pope arranged a swift permission, and within three months the couple were formally separated in 1844.

Cornelia moved with the baby and his nurse into a retreat house at the convent at the top of the Spanish Steps. Adeline went to the convent school, where Cornelia taught English and music. Pierce received the tonsure (Until it was abolished by Pope Paul VI, tonsure, the removal of hair, marked a man’s initiation and eligibility for ordination to the priesthood). He took up theological studies, still hoping to become a Jesuit. The Vatican had arranged that once a week he could visit his wife and children; the Jesuits disapproved of such frequent contact.

Entering the Sacred Heart Convent 1844

Cornelia had one final talk with Pierce before he took major orders, pleading with him to reconsider the break-up of the family and to return to a normal family life. But he insisted on taking Holy Orders.

Before Pierce could become a priest, Cornelia was obliged to take a vow of chastity and encouraged to enter a religious order. In April 1844 Cornelia entered the Sacred Heart Convent at the Trinita dei Monti under special conditions. She took her baby son, Frank, with her. Cornelia was not happy, but she lived there for two years. In July 1845 Pierce was ordained in the convent chapel and said his first Mass, giving his daughter her first holy communion, while Cornelia sang in the choir. She was 36 and had to work out her own future.

Steps:Wikipedia

The Society of the Holy Child Jesus (SHCJ) founded in 1846

The Cardinal Vicar of Rome assured Cornelia that her first duty was to care for 10-year-old Adeline and 5-year-old Frank, and that she was under no obligation to become a nun. She was however, invited to England to educate Catholic girls and the poor. She was helped by Pierce, who was on his way to England himself as chaplain to his sponsor Lord Shrewsbury.

Shrewsbury had publicised the conversion of Pierce from Anglicanism to Catholicism as a sensational coup.

Cornelia drew up a set of rules for a new religious congregation, which she wanted to call Society of the Holy Child Jesus. To avoid scandalising English Protestants, Bishop Nicholas Wiseman put an end to the visitation permission that the couple had had in Rome. The bishop ruled that correspondence would be their only contact in the future. To Cornelia’s anguish, Bishop Wiseman also insisted that she send Adeline and Frank away to boarding school.

In 1846 she was chosen to establish an order of teaching nuns among English Catholics and Irish immigrants in England. The order was established in 1846. In 1847 she took vows and was made first superior of the Society of the Holy Child Jesus.

Cornelia was sent to a large convent at St. Mary’s Church in Derby. Soon she was running a day school for 200 pupils, an evening school for factory women and a crowded Sunday school programme, as well as training novices to her Society of the Holy Child Jesus.

Pierce changes his mind!

Within two years however, Pierce was creating difficulties for Cornelia. He was disillusioned and uncertain both about his own vocation to the priesthood and by hers to religious life.

After a year of total separation, Pierce arrived unannounced at the convent to see his wife. Cornelia was upset and told him not to repeat his visit. He wrote her a letter of reproach, and she replied with bitterness, acknowledging his continued physical attraction for her and her own difficulties in overcoming it.

In December 1847 she took her perpetual vows as a nun and was formally installed as superior general of the society. Pierce did not attend the ceremony. Apparently he was jealous of Bishop Wiseman’s jurisdiction over his wife.

In January 1848 he removed the children from their schools without informing Cornelia. He put six-year-old Frank in a secret home, while taking Mercer and Adeline with him to Europe. He hoped that Cornelia would follow. Instead she vowed to remain faithful to her obligations as Superior of the new community.

This left her with two choices: give up her religious life to be with her children or give up her children. In the face of this dilemma Connelly wrote in her diary;

‘I Cornelia vow to have no future intercourse with my children and their father, beyond what is for the greater glory of God, and is His manifest will through my director, and in case of doubt on his part through my extraordinary [confessor]’.

She never saw her son Mercer again.

Pierce went to Rome, posing as the founder of the Society of the Holy Child Jesus. He made a presentation, purporting to be the founder, to the Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith. He hoped that this would help him gain control over his wife. His efforts were thwarted when Cornelia heard of them; but he remained registered as the society’s co-founder, which was to cause considerable confusion in the future.

On his return Pierce called on Cornelia, bringing her a gift from Pope Pius IX; but she refused to see him unless he agreed to return Adeline to her care. He was livid when Bishop Wiseman, unable to meet expenses in connection with the schools, had Cornelia move her nuns to St. Leonards-on-Sea in Sussex. Pierce was convinced that this was a ploy by the bishop to gain greater control over her.

The Lawsuit

Pierce pressed a lawsuit against Cornelia that gained notoriety in England. “Connelly v. Connelly” was a major scandal which Pierce claimed Cornelia could avoid only by returning to live with him. Lord Shrewsbury asked her to leave England to avoid embarrassing the entire Roman Catholic Church in England. She refused, believing this would betray both her vows and her institute. Bishop Wiseman supported her decision and provided lawyers for her defence. The statement to the court, signed by Pierce entirely omitted his conversion to the Catholic Church as well as the separation and his ordination as a Catholic priest. It petitioned that Cornelia be “compelled by law to return and render him conjugal rights“.

Cornelia’s lawyers provided the facts that had been omitted and cited the legal separation granted them in Rome. After a year the judge ruled in favour of Pierce saying that the decree of separation from Rome did not hold up legally in an English court. Cornelia had two options: return to Pierce or prison. Her lawyers immediately appealed the case to the Privy Council.

Popular opinion favoured Pierce, and on Guy Fawkes Day, marchers carried effigies of Wiseman and Cornelia through Chelsea. She and the bishop were denounced from Protestant pulpits. Eventually, the Privy Council suspended the judgement favouring Pierce. It ordered him to pay the costs to date of both parties as a precondition for a second hearing. She was in effect the winner and could not be forced to return to him. But she could not regain custody of her children, since under English law, a man’s wife and children were his property.

Mercer was sent to an uncle in the US, and Frank was placed in a school.

Pierce himself earned a living from writing tracts attacking Jesuits, the Pope, Catholic morals and (the now) Cardinal Wiseman, which all served to keep Cornelia in the public eye to an extent where she had to take precautions against abduction by her husband.

When the case was dismissed finally in 1857, Pierce took Adeline and Frank abroad. He kept Adeline with him while Frank settled in Rome, becoming an acclaimed painter. Devoted to his mother, he blamed the Catholic Church for having destroyed his childhood home and his parents’ lives.

Cornelia never saw Mercer again; he died of yellow fever in New Orleans, aged 20.

The alienation of her children was the greatest suffering she endured. Cornelia Connelly herself stated that the Society of the Holy Child was ‘founded on a broken heart’.

Pierce, for the rest of his life, conducted a public campaign of vilification against Cornelia.

Cornelia devoted her energies to the expansion of her order, which grew rapidly. After the original school at Derby was moved to St. Leonards-on-Sea, Sussex, in 1848, a number of other schools were opened in London, Liverpool, and Preston and in Toul, France.

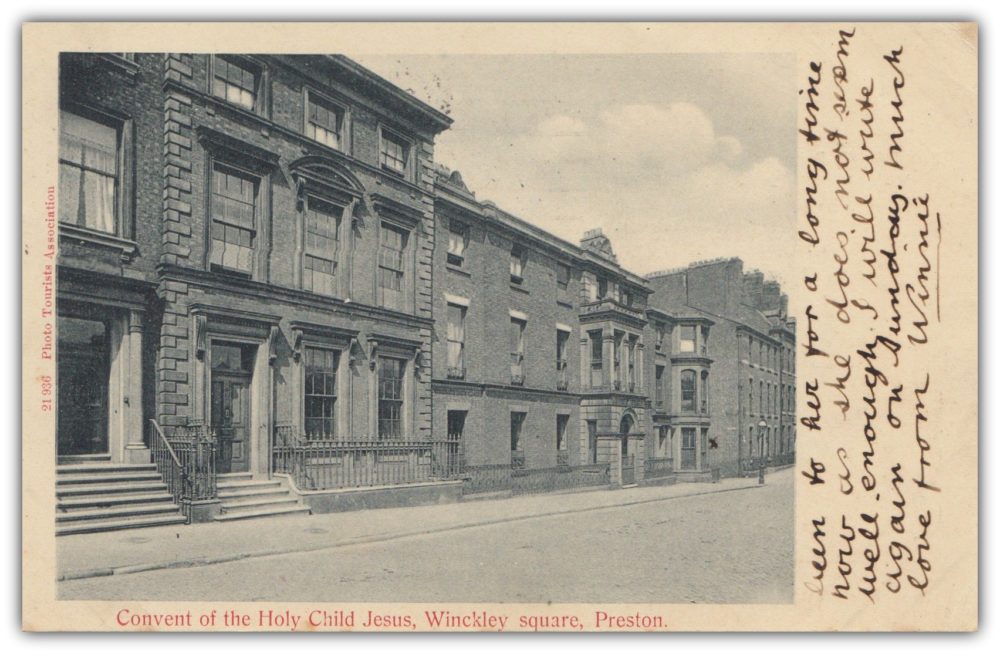

The Society of the Holy Child Jesus in Preston

Cornelia shaped her philosophy of education based on her life experience: the education of students would be best accomplished in a setting of trust and caring attention for each student.

Two years after the founding of the SHCJ, the Jesuits in Preston invited the Society to take responsibility for Preston parish schools. Cornelia was the driving force behind the establishment of Convents of the Holy Child Jesus. In 1853 five sisters arrived in Preston setting up home in St Ignatius’ Square. More sisters arrived the following year and between them they taught in all three Jesuit parishes – St Ignatius’, St Wilfrid’s and the newly established St Walburge’s. They formed three convent schools: St. Walburge’s 1853, St Mary’s 1871 and English Martyr’s 1871.

In the 1850s Preston was developing rapidly. Work for many was in the mills and living conditions were grim. The children in the schools had first-hand knowledge of destitution, unemployment, homelessness and hunger. So the sisters, alongside their teaching, tried to respond to the social and spiritual needs of whole families. They contributed food and other material help, and set up night schools, and Sunday schools that taught much more than the catechism. Cornelia visited Preston more than 34 times.

Winckley Square Convent 1875

The sisters paid £2,000 for number 22 and rented number 23 which was the former home of Thomas Batty Addison, once the Recorder of Preston. The convents at St Walburge’s, St Ignatius’ and St Wilfrid’s merged into one community: the schools continued as before.

In 1876, soon after the house in Winckley Square was established there were 26 sisters living there. The new school was for ‘young ladies’ with about 50 pupils, half of whom were boarders. As the school grew, ultimately the order owned the whole block from East Cliff to Garden Street, down Garden Street and along Mount Street.

Winckley Square flourished, providing, as Cornelia Connelly intended, an education that helped students to ‘grow strong in faith and lead fully human lives’. The school reached its peak of 850 pupils in 1962. In 1978 as part of the reorganisation of Catholic Education in Preston it was wound down merging with The Catholic College and Lark Hill Convent to become what is today Cardinal Newman College. The site closed in 1981.

As well as having a boarding and day school for ‘young ladies’ in the Square, the sisters also educated pupil teachers and were the headmistresses of many of the Catholic primary schools in the town. For more than a century, as the town expanded, sisters took responsibility for school after school in the newly founded parishes: the Sacred Heart, the English Martyrs, St Joseph’s, St Mary Magdalene in Penwortham, St Anthony’s Cadley, St Bernard’s Lea, as well as in the long-established St Mary’s in Friargate. Later they also taught in the Catholic secondary modern and comprehensive schools. Their contribution to Catholic education and parish life in Preston was immense.

By the middle of the twentieth century, lay people (many of them Holy Child educated), assumed the headships of the schools. The number of Holy Child sisters in the town decreased, the sisters moving first to East Cliff and then to St Austin’s Place where the community participated in the life of the parish much as the earliest sisters had done.

Educational philosophy

Despite the strained economy Cornelia insisted on maintaining day schools for those who could afford tuition, as well as free schools for those who could not. For her brightest female pupils she introduced Greek and Latin writers in translation – courses that were otherwise reserved for male pupils. During the Darwinian revolution she had her pupils learn geology. She encouraged them to engage in art, music and drama; even to dance the waltz and polka, as well as playing whist!

Her attitude towards discipline was unusual in that a school to her was meant to be a home, with the nuns as mothers who should love, trust and respect their pupils. Disliking the customary convent rules of constant surveillance, she encouraged mutual trust and respect for different talents.

Death and Legacy

Cornelia’s health was a nagging issue over many years. She suffered from rheumatic gout, and bronchitis. She died on 18 April 1879 at St Leonards-on-Sea, Sussex and was buried at Mayfield. Later her body was transferred to a tomb in the fourteenth century chapel.

The order of the Sisters of the Holy Child Jesus is still active around the World, although the last two sisters left Preston in 2015.

And what of Cornelia and Pierce’s children?

To recap, Cornelia and Pierce had five children; Mercer, Adeline, John Henry, Mary Magdalene and Pierce Francis (Frank). Mary died after only two months and John Henry died aged two. Mercer died of yellow fever in New Orleans at the age of 20, completely alienated from his mother.

Adeline and her youngest brother Frank lived with Pierce for many years in Florence.

Adeline ended up as her father’s companion for 35 years. Pierce’s brother George had sent money for ‘Adie’. He wrote to Pierce after Adeline visited him.

‘I consider you have utterly sacrificed her to your own selfish enjoyment of her company…Adie…had not decent or sufficient clothing…The money I send was for this purpose.’

Isabella, Cornelia’s half-sister, made Adie a beneficiary in her will.

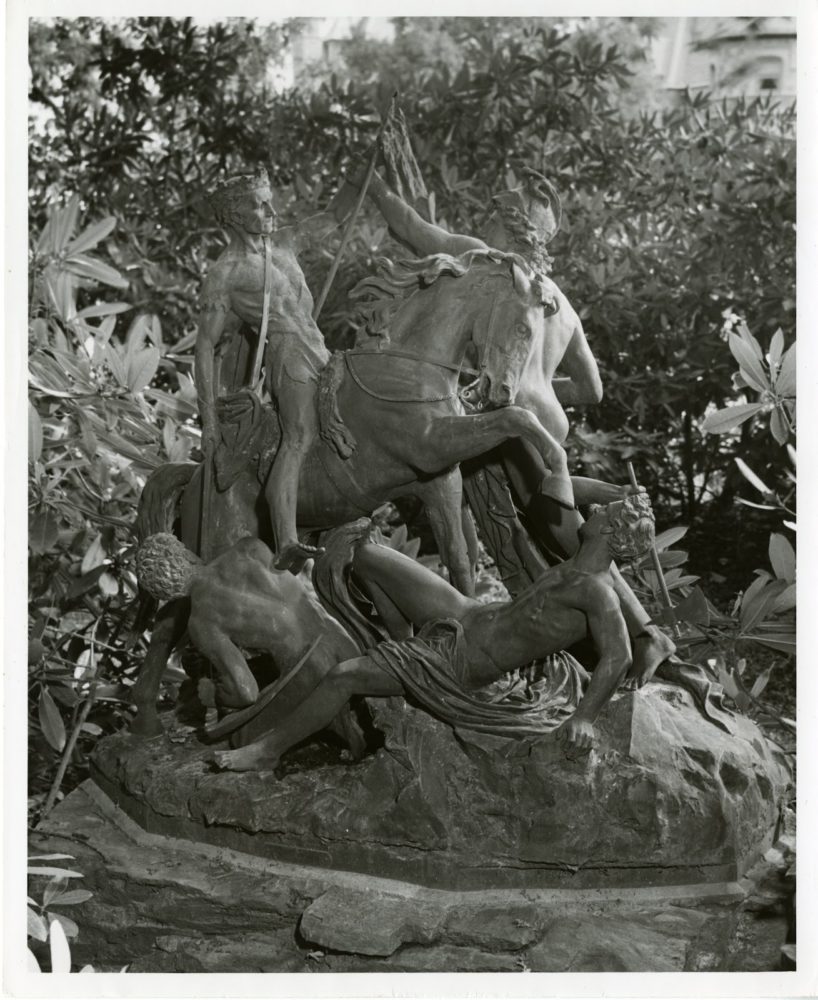

Frank remained firmly anti-Catholic. He became a sculptor of some note. In 1871 he exhibited several portrait busts at the Royal Academy in London. These caught the eye of Queen Victoria, who commissioned a bust of Princess Louise from him. He returned to Italy around the time of his father’s death and was later buried there himself—in a Protestant cemetery. Although he didn’t marry, he had a daughter, Mariana, who later became Princess Borghese.

A group composition that features six different figures: Death, Death’s horse, Strength, Courage, Perseverance and Hope: SHCJ website

Mariana felt that the sculpture should be in the hands of the Society of the Holy Child Jesus and she gave it to Rosemont College, Pennsylvania. Through Frank’s daughter Mariana, Pierce and Cornelia still have direct descendants.

Postscript: Pierce by 1868 had become rector of the American Episcopal Church in Florence. He died an Episcopalian.

Acknowledgements

Society of the Holy Child Jesus in particular Sr. Judith Lancaster for all her help.

The SHCJ have kindly agreed to let us use photographs from their website. The website is an excellent resource with many more photographs of Cornelia’s family.

By Patricia Harrison