Geology

We are very grateful for the enormous help provided by GeoLancashire and in particular to Jennifer Rhodes, the Secretary.

The great majority of this section is drawn from their work with their permission and support.

Preston’s location was, and remains, a key factor in its development. Preston became an important settlement because of its position at a vital river crossing point between the Pennine uplands and the Ribble estuary with the marshes of the coastal plain.

Preston’s position made it a ‘hub’, a market centre, where trade could take place. The Ribble formed (and still forms) a natural barrier to the movement of people and goods. The Ribble west of Preston, with its estuary and the marshes along both banks, proved too wide to bridge.

However, at Penwortham, the river could be crossed. Visit Old Penwortham Bridge at very low tide and you can see the river is flowing over solid bedrock, Red Triassic Sandstone. The Ribble could be forded at this point and the rock later provided a firm basis for a bridge.

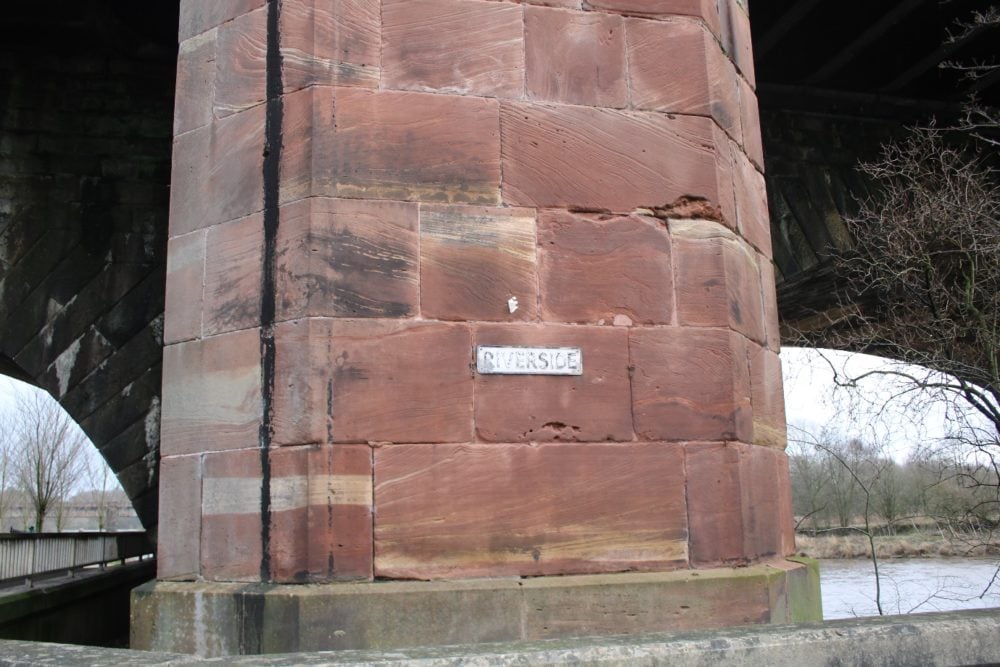

You can see the Red Triassic Sandstone incorporated into the Old Penwortham Bridge and it is highly visible on the west side of the West Coast Main Line bridge over the Ribble; facing the Continental pub on Riverside

The red Triassic bedrock is a visible part of the Sherwood Sandstone on which the whole of Preston stands. Sherwood Sandstone was formed between 200 and 290 million years ago when the area we now call Preston was part of one huge continent and had a climate similar to that of the Sahara Desert. In places these local sandstone beds are up to 600 metres deep.

Read more about how Preston’s site was carried by plate tectonics.

Sherwood sandstone provides a solid basement for several towns in the area. Preston and Liverpool both owe their sites to outcrops of Sherwood sandstone, which stand above the low lying surroundings (where less resistant rock has been eroded more easily). Sandstone can be both permeable and porous so does not become waterlogged like clay. Where an outcrop forms relatively high ground, especially at a river crossing, it provides a base for bridge supports and a defensible site. Buildings are much more likely to be above flood levels. So – many positives and very few negatives.

The development of the town of Preston was therefore concentrated on the higher land, rather than in the valley of the Ribble.

Prior to the ‘training’ of the River Ribble in 1853 and the subsequent development of the docks and extension of the training walls towards the estuary in the 1880s, the land alongside the Ribble was marshland. Marsh Lane has the clue in its name; it ran to Preston Marsh by the river.

Lea Marsh and Clifton Marsh lay west to the north of the river and the area south of the Ribble still has very little development and few roads. Hutton Marsh, Longton Marsh, Hesketh Out Marsh, Banks Marsh and Crossens Marsh are flat areas of saltmarsh and mud flats whose only features are the constantly shifting channels.

High on the outcrop the town was free from flooding. Building was concentrated on the three main thoroughfares of Churchgate, Fishergate and Friargate.

Development was also to take place on the land overlooking the valley of the Ribble. Avenham Walk was popular with wealthy residents from the 17th Century and the views afforded from the top of the cliffs influenced the building of large properties along Ribblesdale Place, The Cliff and Ribble Bank.

Travelling between Fishergate and Avenham Walk proved challenging. A small river/ large stream, the Syke, had carved out a valley along the ridge. The land alongside the Syke was boggy. Snipe (a wading ‘game’ bird) nested and fed there. Women and men had to negotiate the Syke, dressed in their finery, hoping ‘to see and be seen’ while promenading along Avenham Walk.

Longridge Stone

The uplands close to Preston are the source of stone known as Pendle Grit. Longridge in particular was quarried for this. Pendle Grit is known locally as Longridge Stone. It played a major part in the construction of public buildings in Preston. The Harris Museum is made of Pendle Grit. The steps leading up to Lord Derby’s statue on Miller Park are also Pendle Grit, quarried in Longridge. In Winckley Square the stone walls to the north and west, in which the oldest railings are set, are Longridge Stone.

Fulwood Barracks and the Railway Station in Preston, as well as Blackpool Town Hall, Bolton Parish Church, Liverpool and Fleetwood Docks and many other major buildings in Lancashire are built with Longridge Stone. There were numerous working quarries. Including one called Lords Quarry, on land owned by Lord Derby.

The Longridge Heritage Committee has produced Trails; the first of which includes the area of the quarries worked for Longridge Stone.

The stone was quarried and then transported to Preston to join the rail network.

Initially this was via the Preston & Longridge Railway which opened in May 1840. Horses pulled the trains consisting of empty wagons up the hill from Preston to Longridge. There the wagons were filled with stone. The horses were put in special carriages (known nationally as Dandy carts) and given a ride back down. Gravity carried the full trains down the hill back to Preston. Steam replaced horse power in 1848.

By Steve Harrison