The History of the Gardens

Wherever we make a home there is the urge among many of us to make a garden; it might be for growing fruit and vegetables, for a pleasant place to have a meal outside or for a quiet place to sit, relax and reflect.

Town gardens answer all these needs; in Pompeii and Herculaneum the town dwellers put their small, enclosed gardens to all these uses. In fact, the layout of these intricate urban gardens may be said to have influenced every other down the ages. The elements are simple – sand or gravel paths, turf kept short, a tree or two for shade and blossom, flowers and herbs to pick and, as a luxury, water in the form of a pool or fountain.

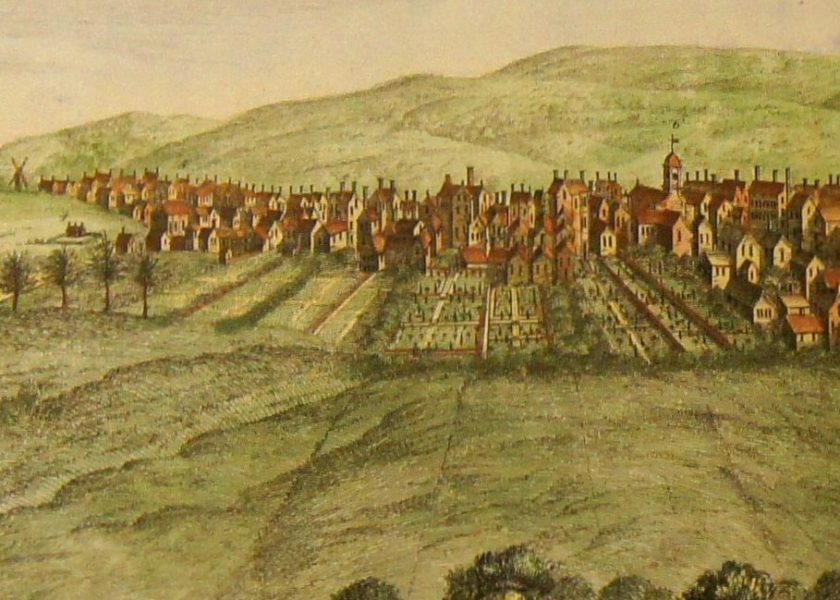

The model for our English town gardens originated with medieval burgage plots; these are evident on early Preston plans, stretching away from the houses on Fishergate in long, narrow strips.

The divisions within Winckley Square echo these plots. Documents and archaeology indicate that urban gardens were used for:

- Growing food

- Keeping animals

- Small-scale crafts and industries

- A drying ground where washing was laid out

- Rubbish and night soil disposal

Even in the early years of the 20th century these practices were usual; at Port Sunlight, where Lord Leverhulme built spacious housing with generous front and back gardens for the workpeople, an order was issued by the village committee banning these practices in the front gardens, on penalty of a fine.

City Squares

The grander houses in cities such as London, Edinburgh, Dublin, Bristol and Liverpool began to be built around a planted square. Georgian builders found that the value of a house increased if a park-like setting was offered; in addition, wide avenues and open spaces were considered beneficial to health and a counterpoint to the many odours of a town.

Most garden squares were laid out as one open space, offering trees for shade, a central fountain or pool and squares of turf surrounded by linear flower beds. An Act of Parliament in 1726 enabled the residents, rather that the landlord, to maintain the square.

William Cross had trained in London as an attorney and had seen the new style of town planning taking shape – Bedford Square (1775-1780) was the first to be designed with architectural uniformity and it set a pattern. The garden square in Preston may have been intended to follow the London model, emulating the elegance of Russell, Cadogan or Bloomsbury – the latter having a formal (straight) lime tree walk. There were more than 30 Squares in London by the time William Cross embarked on creating one in Preston.

The Square divided

William Cross sold individual plots within the Square. The sale included the requirement that the buyer had to provide a pavement and a road between his (It was always his in the early developments) home and his garden. However, it is clear from the Regulations of Winckley Square that William Cross wanted the owners to share at the creation and upkeep of a shared space, as in London.

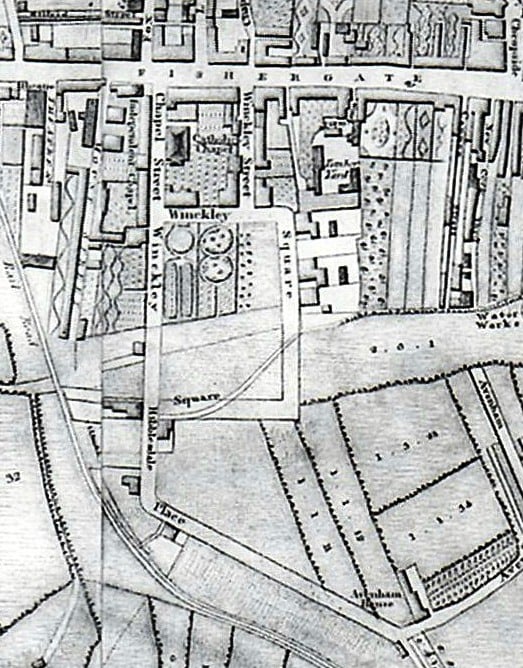

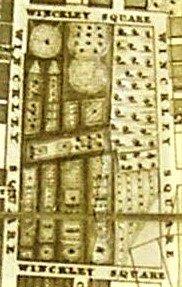

By 1822 just 3 of these strips had been sold, at the northern end, and on the map by Wm Shakeshaft of that date the plots display the simple, geometric layout of the Georgian town garden. Even the avenue in Bloomsbury Square is echoed in Winckley’s north-eastern plot. An avenue of trees follows the line of Winckley Street and may have served as a continuing avenue through the gardens.

The winter scene could have included:

- Topiary trees of bay laurel,

- Standards of holly (striped with silver or gold),

- Box clipped as a hedge, globe or pyramid, laurustinus as a standard,

- Herbs which retain their foliage in winter such as rosemary, germander, hyssop and sage.

Summer flowers could have included:

- Astrantia,

- Dicentra,

- Digitalis,

- Eryngium (sea holly),

- Hardy geraniums (single and double),

- Iris,

- Peony,

- Phlox,

- Roses (single, double and striped),

- Scabious,

- Stachys lanata (lamb’s ears)

- Veronica.

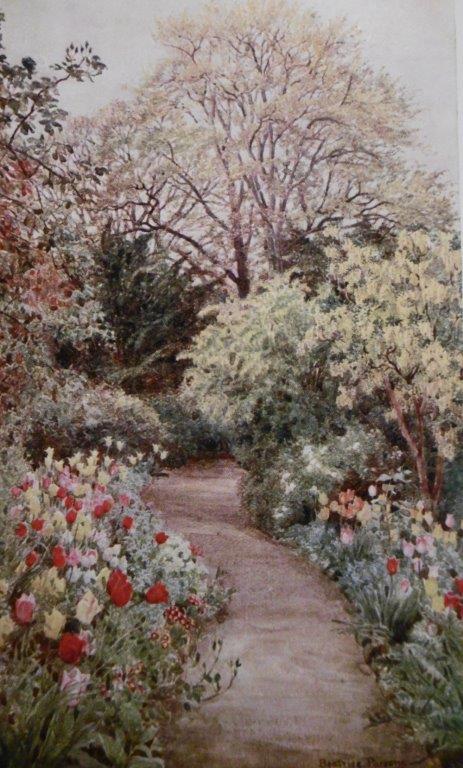

Climbers available were honeysuckle, grape vine, summer jasmine and, of course, more roses including the Great Maiden’s Blush. Apple, plum and pear trees provided spectacular spring blossom, accompanied by many varieties of Dutch bulbs such as tulip, narcissus, scilla and single hyacinth.

Into the Regency Period

The Regency Period is a loose term which describes a style rather than actual years and can cover 1785 to 1837. The Square gradually filled with harmonious houses of a uniform architectural style. More plots were sold and were tended by individual owners to their own requirements. By 1836, a plan by J. Myers shows 8 long, narrow gardens; one large plot has trees arranged in domino fashion which may indicate an orchard; others are divided into many small square sections which could have been for fruit and vegetables.

We know from Samuel Leach’s diary that the maids at 5, Camden Place (on the corner of Camden Place; overlooking the Gardens) had washday every Monday. They rose at dead of night, washed and then put out the wet washing in their strip of garden to dry. They had to bring it in before dawn to keep up appearances.

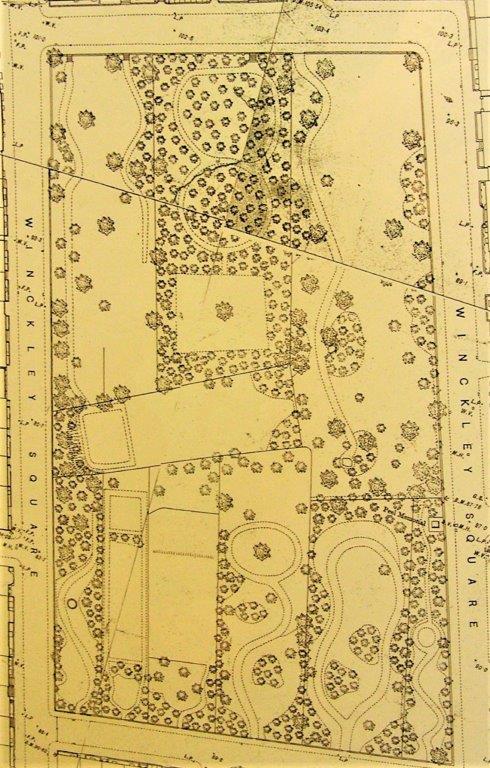

Detail from J.J. Myers, (1836), A Plan for the Mayor, Burgesses and Aldermen of Preston. Cutting grass had become easier since 1830 when Edwin Beard Budding invented the lawn-mower; he worked in a velvet mill and observed how a looped fabric was turned into velvet by shearing the top with sharp blades on a roller. Before then grass was cut with a scythe or kept short by a goat.

Victorian Developments

As the Victorian age progressed (1837-1901) the availability of plants rose exponentially. A slow trickle of exotic plants had entered Britain from South Africa, eastern America and Europe until the 1860s, enhancing our gardens with trees, shrubs and bulbs. Then China and Japan gave restricted entry, to medical people at first and then to traders. A great array of beautiful plants came to our shores including camellias and wisteria (Japan), rhododendrons and pieris (China), cypresses and cedars (western America) and fuchsias (Mexico).

Residents in Preston were able to purchase much of this cornucopia from the nurseries trading beside the river on the former Avenham Fields.

Change in Garden Fashion

A great change in garden fashion took place in Georgian and Regency times but came late to gardens in Preston. Owners of large gardens such as Astley Hall, Chorley and Woodfold, Blackburn employed the landscape ‘improvers’ John Webb and William Emes to create parkland in the Picturesque style; the aim was to make a large garden resemble natural countryside, with a stream, a serpentine lake, acres of turf and stately trees arranged singly and in copses.

Being difficult to translate in an urban garden, an ingenious Scottish designer J.C. Loudon coined the term Gardenesque and devised a layout where serpentine paths wound their way around a plot and through shrubberies. This is what we see on the map dated 1892.

There was no longer a need to grow food in the urban garden since the opening of Preston market in 1875.

The new garden feature, the shrubbery, could display lovely spring subjects such as flowering currant and Japanese quince, summer ones such as fragrant lilac and orange blossom, and the autumn foliage of azalea and maple.

There was abundant water beneath these gardens. In addition to the ‘Syke’, which ran in a culvert east-west across the middle of the Square, there was a well in the north eastern corner. By 1854 at least, there was a splendid fountain in the south western corner, seen on the engraving of that date by Joseph Rock; its high jet could only have been achieved once a piped water supply had arrived in town. It had an elaborate base and filled a wide round pool. On the same engraving, an officer stands at a gate and is responsible for only allowing into the square those who had the right to enter. From the outset the Gardens were behind railings and access was restricted to residents with a key for the gates.

The huge growth of Preston brought about by its cotton mills caused changes in the town centre. Pollution from domestic coal fires and from the mill engines drove people out of town to the suburbs, where, as an added benefit, plants grew better too. Winckley Square waned as the core of Preston society. Successive maps after the First World War chart the decline of these unique gardens. Divisions started to disappear as plots changed hands. In 1951 an agreement was reached between Preston Borough Council and the owners that the council should undertake to maintain the gardens as a public amenity; on the OS map dated 1968 all divisions have been removed and paths have been established connecting the various streets.

A number of the ‘plots’ in the garden remain in private ownership. They are leased to the City Council. A 25 year lease agreement was a condition of the funding from the Heritage Lottery Fund.

By Elaine M Taylor

Useful Sources

English Heritage, Urban Landscapes, English Heritage, London. 2013, reissued 2017.