Winckley Square Gates Again!

Local newspapers in the 19th Century took a keen interest in the development of the town and in the words and actions of the leading figures. Reports were lengthy and detailed and the names of those present were listed.

The ‘Preston Chronicle and Lancashire Advertiser’ of May 18th 1850 carried a report of a meeting of the ‘Commissioners for the Improvement of the Borough of Preston in the County Palatine of Lancaster’ which was held to decide on whether the south side of Winckley Square should be designated a public highway. The title of the report was The Winckley Square Gates Again which speaks volumes.

The context for the meeting is important. In 1844 The Chronicle had heralded the plans for the final parts of Winckley Square with the words:

“ It is gratifying to our local pride, to witness the alterations and improvements which have been projected and undertaken in our good town, they are evidence of its increasing prosperity, of the extension of its trade, and the activity of its business. In Winckley Square, James German, Paul Catterall and Thomas Ainsworth, Esqrs, are about to erect handsome mansions, which with the intended buildings for the Literary and Philosophical Institution and News Room, will complete three sides of the area, leaving only a small vacancy on the west, short of finishing the square”

Saturday, April 27, 1844 Column 4 Issue 1652

James German then built 14 Starkie Street (what is now Starkie House) on the corner of Winckley Square and Starkie Street. As others had done before him he built the property with its entrance on the side street (14, Starkie Street) so as to maximise the potential of windows overlooking the Gardens.

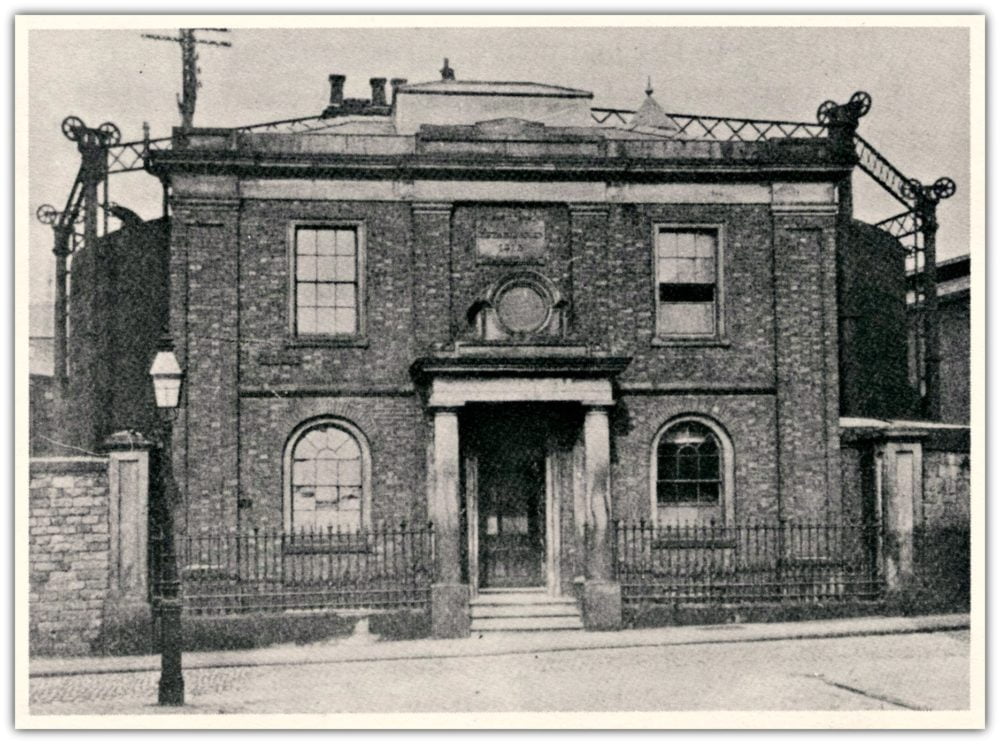

Paul Catterall built 13 Winckley Square (what is now Charnley House) at the same time.

On the east side of the Square three buildings were built which have all been demolished:-Thomas Ainsworth’s home aka the Italian Villa

The Literary and Philosophical Institution along with the Winckley Club were two Gothic style buildings for the use of Preston’s most influential men.

These developments of the 1840s marked a step change from the original plan for a Square surrounded by houses. The Chronicle regarded it positively.

Ellen Cross, in selling plots of land around the Square for building, required the purchaser to be liable for the construction of a pavement and a road in front of their property. She retained ownership of the land on which the road was laid. In effect it was leased to the purchaser of the building plot. In the case of James German and Paul Catterall they owned the plot on which their homes were built and they owned a portion of the Gardens facing their property but they did not own the road between. However, they were responsible for its development as road and pavement.

By 1850 the properties were all built and it was proposed that the road in front of the south side properties should be designated a public highway. Today we would talk about a road being adopted. Then as now that would mark the transfer of the road from private ownership to public ownership and the cost of maintenance would also pass from the private to the public purse. Once a road was designated a public highway the public enjoyed a ‘right of way’. This included pedestrians and those with horse and cart or carriage.

One of the functions of the ‘Commissioners for the Improvement of the Borough of Preston in the County Palatine of Lancaster’ was to determine which roads should be declared public highways.

Previous discussions had taken place as to whether the south side of Winckley Square should be designated a right of way. James German had erected gates outside his property to prevent free movement along the south side.

Gates were also erected at the south west side of the Square.

The meeting in 1850, reported in the Chronicle, was attended by over 70 of Preston’s influential men (only men) all of whom had a vote.

What complicated matters further was that Ellen Cross had died in 1849. As Ellen Cross’ intentions were relevant to the debate her death allowed for speculation as to her intentions.

Finally it is important to recognise that other changes were taking place which had an immediate impact on Winckley Square.

The first railway had arrived in 1838. The East Lancashire Railway was now (1850) developing its own station east of the existing station. A gas works had been built at the site of the current Avenham multi-storey car park.

The gas works needed coal for the manufacture of gas. The shortest route from the railway to the gas works was along the south side of Winckley Square. Instead of gazing out on their personal plots in the Gardens, James German and Paul Caterall faced the prospect of gaping at a procession of horse drawn carts carrying bricks, cannel (a form of coal closer to shale but excellent for the manufacture of gas) and other loads.

What follows is a summary of the debate and decision. It cannot capture the style and detail of the original.

The Debate

On the 8th May 1850 at 10 in the forenoon (before 12 noon) the commissioners met. Six of them had proposed that the South side should be designated a public highway.

William Ainsworth (Owner of the Italian Villa, Winckley Square) was voted into the chair. Over 70 attended, all men.

William Banks: for the motion:

William Banks spoke for the motion. He acknowledged that some, including barristers present, had argued that it was not lawful to join one road to another without the consent of the landowners however, he contended that this was not the case.

It was the intention of some present to block the route between the west and east sides of Winckley Square. Mr Banks pointed out that the Police Act meant that if the commissioners decided a paved road was suitable then it could be declared a public highway.

Mr Banks went on that the late Mrs Cross (Ellen Cross) had consented to the south side being dedicated to the public and it was already paved. He added that even though Mrs Cross owned the soil she did not have the right to ‘stop up a street’ which had been used by the public for some time.

Banks sought to undermine arguments previously advanced by Mr Catterall. Despite James German (owner of what is now Starkie House on the corner of Starkie Street and Winckley Square) having had posts placed in the carriageway to obstruct traffic- for years prior to this, the route had been used by the public and this was enough for the commissioners to rule it a Public Highway. He added that Mrs Cross had roads constructed so that the plots around the Square could be sold for buildings. Those who now owned these buildings had not gained ownership of the street in front of their properties.

Banks intimated that the reason Catterall wanted the south side blocked was the fear of cannel. He went on to say that Cannel Coal would not be transported past the south side homes. He argued that the East Lancashire Railway would not be carrying cannel which comes from Wigan and not from east Lancashire.

Another previous argument he rebuffed was that the houses on the south side were particularly fine houses. Banks pointed out that other fine house were around the Square but the streets in front of those were not blocked.

Then Banks turned to the argument that those in the houses along the south side would suffer if the road were blocked. How would domestic coal & milk be delivered? Back Starkie Street was not a public highway and was used by gentlemen to ‘clean their carriages and shake their carpets’

He summed up by saying that there would not be much carting of bricks or coal, that the public had a right to travel there and that the owners of other properties on the south side would suffer if the road were blocked.

He ended by accusing his opponents of spreading falsehoods and of soliciting commissioners to attend in order to vote against the motion. He warned that the promise previously made of a pathway for pedestrians was false as the space left was too narrow. He also recounted a conversation he had had with James German but it was in such a low voice the reporters couldn’t hear it!

Peter Caterall responded: against the motion.

He demonstrated that he had personally stopped wagons from travelling along the south side. He argued that such actions proved that the public had not been ‘uninterrupted users’ of the street, contrary to what Banks asserted.

Caterall then damned with faint praise Mr Banks’ legal arguments. He pointed out that the commissioners had a clerk, Mr Palmer, present to serve them and that he should be asked for a legal view on the question.

The Chairman agreed but there were interventions before Banks challenged Caterall’s right to pose a question to Mr Palmer. The reporter writes that there were various challenges and ‘a great deal of confusion’

Palmer pointed out that in the past anyone could lay out a road and pave it and immediately the town would become liable for its repair and upkeep. The town had no wish to become liable for the repair of private streets at the public expense and had passed an act to avoid this. The upshot was that unless a formal dedication of a road as a public highway took place then it could be assumed that no right of passage for the public existed.

Peter Caterall went on to say that he would fight any decision by the Corporation to declare his land a public highway. He would fight it through the courts.

He went on to ask who needed this road to be a public highway. Those coming from Church Street can travel down the east side of the Square and those from Fishergate down the west side. Mr Wilkie declared HE wished to use the road but Caterall replied that he could do so with pleasure – as a pedestrian.

Caterall went on to declare that the owners on the south side objected to brick & coal carts coming between their homes and their gardens. He added that no one would gain from the road being designated but homeowners would suffer injury. As Mr Cross (heir of Ellen Cross) had not supported the motion of Mr Banks and as the clerk too had not supported it, Caterall proposed an amendment – to reject Banks’ motion.

Questions were posed including whether the owners of the properties would let neighbours pass.

‘Oh Yes’ replied Catterall.

Who owns the land between the houses and the gardens?

Mr Cross’ solicitor confirmed to the meeting that since the death of his mother, Mr Cross now owns the land between the houses and the gardens and he does not give his assent to it becoming a public highway.

James German then spoke at length. He guaranteed that any person living on the Square would enjoy the right to pass along the south side.

He felt that the people of Preston would enjoy looking at the fine houses that had been built on the south side and which completed the magnificent Square. He hoped operatives would enjoy walking past the houses and admiring them. Their pleasure would be badly affected by carts carrying bricks and coal.

He claimed to have as much right to the enjoyment of his private road as to his drawing room.

German and Caterall agreed that Back Starkie Street could become a public highway. They pointed out that this gave the best of all worlds. Those on foot could pass by the front and carts by the back.

A Mr Walmsley who had initially been minded to support the motion indicated he would now support Caterall’s amendment on the grounds that he suspected the East Lancashire Railway Company was behind this motion so they could have their coal wagons pass on the south side. He would not be tool of the ELR!

Caterall’s amendment was passed by 52 votes to 22.

Polite society and self-interest

As well as the substance of the Commissioners’ debate and vote, the report itself provides insights into the conduct of meetings and the contortions speakers undertook to promote naked self-interest.

The Chairman, William Ainsworth, said that ‘He was anxious that the meeting should be conducted with the greatest good temper and good humour.’

Mr Banks concurred with this as ‘he came here with no other feeling than that of serving the public rights.’

Mr German made it clear he would not ‘attribute any motives of spleen to those gentlemen’ who had moved the motion. However, he went on to say that ‘occupying the high public position he had the honour to fill, he trusted they would believe that he acted from really disinterested motives.’ (He was mayor at the time, Peter Caterall would be mayor in 1852/3).

Nonetheless he added ‘it seemed to him some of the commissioners were desirous of doing a dying act – a sort of heroic act that would distinguish them at the close of their careers’

Philanthropy?

‘It would much gratify him to see the public have the full enjoyment of walking past these houses, and looking upon what he considered one of the greatest ornaments of Preston, namely – the completion of Winckley Square.’

Mr German went on to suggest that the houses he and Mr Catterall had constructed would bring immense joy to the workers from the mills who could walk by and look at the buildings.

‘Nothing would give him greater pleasure than to see his operative friends enjoy themselves at looking at the new buildings on the square.’

Mr Walmsley declared he had intended to support the motion but the role of the East Lancashire Railway Company disturbed him. He believed they would want to use the south side as a road for their goods. ‘he objected to allow himself to be made a tool of by any railway company.’ Followed by ‘Hear Hear!’

He added he knew that railway companies ‘had no consciences at all in the matter.’

If you would like to read the full account of this meeting in the original newspaper report:

Download Preston Chronicle 18th May 1850

By Steve Harrison